I Love It When Anons/guests Find My Works And Kudo/leave Reviews, But Given The New Revelation That Elon

I love it when anons/guests find my works and kudo/leave reviews, but given the new revelation that Elon Musk is using bots to mine AO3 fanfiction for a writing AI without writer's permission, my works are now archive-locked and only available for people with an AO3 account.

More Posts from Enbylvania65000 and Others

The Early Therocene: 30 million years post-establishment

Bouncing Bipeds: The Boingos and the Oingos

From the tiny, hopping jerryboas of the Rodentocene would arise the most widespread and dominant of all the herbivores on the planet: the boingos. Descended from the greater skipperroo of the Middle Rodentocene, these bipedal bounders would come to dominate the open plains, grasslands, and savannahs all across Nodera, Westerna, Easaterra and Ecatoria, crossing tthe land bridges of the Late Rodentocene and quickly expanding all across the primary continents.

Today the boingos have become one of the most diverse clades of HP-02017, spanning nearly a hundred species as of the Early Therocene. The largest species, the spotted boingo (Macropodomys giganteus) stands six feet in height and can weigh up to 190 pounds, while its other relatives are smaller, but still far larger than the tiny jerryboas they descended from.

Various species of boingos of this age have since diverged into a wide variety of forms with unique adaptations and lifestyles that set them apart from their relatives. Easily one of the most remarkable species is the streaky zibba (Saltozebroides melanoleuca), sporting bold black-and-white stripes and traveling in large herds numbering in the hundreds. When attacked by a predator, the entire herd scatters and starts bouncing away in all directions, and their erratic movements and dizzying coloration makes it difficult for a predator to zero in on a single target. Others, such as the dusky boingo (Tenuipodomys cinereus) prefer to fight than flee, sporting large claws on their hind legs that can deliver devastating kicks to an enemy.

Some of the boingos have started spreading out from the grassy plains and into other biomes as well. The twinstripe tattoroo (Gracilosaltomys lineaurum) lives in marshy wetlands, where its broad webbed feet keep it from sinking in soft ground and also makes it a surprisingly good swimmer, propelling itself with powerful kicks of its hind limbs. The desert jackaroo (Gymnocaudamys heremus), on the other hand, makes a living in a far drier clime, where its large ears, hairless tail and feet, and light-colored coat help it in losing heat in the arid climates of northern Easaterra.

Meanwhile in the continent of Easaterra lives another, smaller lineage of jerryboas descended from the prairie roobit of the Middle Rodentocene, and closely related to the boingos: the oingos. These smaller cousins of the boingos are endemic to Easaterra, where the only hamtelopes present are towering high browsers: as such, they fill the niche of low-browser and small-scale grazer that are filled by smaller hamtelopes elsewhere.

Various biomes are prevalent in Easaterra, and the oingos have adapted to thrive in a wide variety of them. Scrubland oingos (Minimosaltomys lagoides) thrive in lands dominated by low-lying bushes and shrubs, while the forest oingos (Australosaltomys longuscolli) make a living in tropical forests where they use their longer necks to reach for low-lying branges and bushes in the understory of their jungle home. And in the southernmost region of Easaterra, predominantly icy tundra and permafrost, lives the arctic oingo (Frigorimys glacies), insulated with thick white fur that it sheds in summer and regrows in winter, as well as broad, fluffy feet that prevent it from sinking in the snow.

The tremendous success of the boingos and the oingos revolve around their unique anatomy, namely their growing molars and hopping locomotion. While most herbivorous hamsters have molars with no definite roots and thus can grow constantly like their incisors, the molars of boingos and oingos grow relatively quickly and thus can better handle daily abrasion from the tough stems and sheaths of plains grasses, their favorite food.

Their bounding gaits are also incredibly efficient for traversing the open plains, with spring-like tendons in their hind legs that store energy with each landing and use it to power the next hop, allowing them to bound long distances across the grassland with scarcely any effort at all. This gait also compresses and expands their body with each hop, aiding in their breathing during strenuous activity. With more efficient dentition and locomotion, the boingos have the upper hand in the plains over the hamtelopes, which instead evolve into strange new niches to avoid their competition, such as browsers and small soft-grass grazers, and only on the continents of Borealia and Peninsulaustra, where boingos and oingos are absent, do the hamtelopes get a shot at grassland domination.

But though they look like kangaroos, move like kangaroos and hop like kangaroos due to convergent evolution, the boingos and the oingos are still placental mammals, and thus lack pouches to carry their young. Instead, much like hares and guinea pigs, they give birth to small but well-developed young that are fully-furred and open-eyed upon being born, and within an hour of their birth can already hop about and are able to follow their mother about at only one day old. Boingos and oingos typically give birth to a litter of about three to four, but sometimes as many as eight, and the sight of a mother boingo hopping along followed by her bouncing young ones in single file is a common spectacle across the plains throughout their native continents.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

Chicago Business District, 1898.

10,000 IQ Deduction (EGSNP)

Nonchalant Ashley (Sketchbook)

Larry cleverly deduces that Ashley has transformed herself at the mall and hopes that no one, especially Rich, notices.

Wait, that doesn't sound right.

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Full Boar Action: The Bumbaas

The bumbaas are descendants of the cavybaras that reigned in the Middle Rodentocene as the largest animals alive on the planet. Nowadays, such a distinction is gone, as other lineages continue to increase in size in the vacancy of niches: however, this particular branch of the family is still going strong, especially in the lineage of the bumbaas, adaptable omnivores that thrive throughout Ecatoria but also in Westerna and parts of Nodera too, as the cooling temperatures of the end of the Rodentocene once more resurface the land bridges which allowed new lineages to spread across the continents. And so the bumbaas spread and diversified in the different environments, foraging for grasses, shrubs, roots, fruit, invertebrates and carrion, on opportunistic occasions.

Aside from the desert bumbaa of the Great Ecatorian desert live a wide variety of other species. Other members of its genus, such as the forest bumbaa (Scrofacricetus matatai) are found elsewhere throughout Ecatoria, where, like their desert-dwelling cousin, are also avid part-time insectivores, supplementing their diet of grasses and roots with raiding insect nests: especially termites, whose mounds are abundant and a favorite of the bumbaas who break into the layers of hardened mud using their sharp tusks to access the juicy morsels within.

However, not all bumbaas closely resemble the members of this genus. Some, such as the meenypigs (Porcimys spp.) have become smaller and more slender, becoming tiny herbivores in the dense forests of Ecatoria much like mouse deer do. They feed primarily on mosses and lichens that grow on the forest floor and on the roots of trees and on logs, and with their smaller sizes prefer to run from enemies than fight them, thus favoring a build with longer legs and a leaner body.

But by far the most unusual member of the bumbaa family is the masked luchaboar (Tetracerodontomys venustafacies), a highly sexually-dimorphic species with a distinctive social system, and the only genus of bumbaa native to northern Nodera. Herds are comprised of a harem of up to a dozen females, their offspring, and a single dominant alpha male who stands out with his elaborate weaponry and brightly-colored facial markings that stand him out against the rest of the more drably-colored herd.

Most bumbaas sport only a single pair of tusks, on their lower jaw as extensions of their incisors. However, due to the constant wear and tear of abrasive vegetation on their teeth, the bumbaa's molars have also evolved to grow constantly, like their incisors, to deal with the continuous damage, and in male luchaboars the first pair of upper molars have become tusks as well: sporting a grand total of four. Males put these unusual teeth to good use, as they are fiercely territorial and aggressive: their brilliant facial markings serve as warning coloration to intimidate rivals, which they try to scare off by loud and threatening squeals, but more often than not results in a full-on wrestling match as the two males try to wrestle each other to the ground and jab each other with their tusks, which frequently results in bloody wounds and broken tusks, though as their tusks continually grow these damage is of little consequence as long as the root remains intact.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

The Map and World of the Late Rodentocene

The Late Rodentocene, 20 million years PE, is a world that geologically speaking has changed very little from the time the hamsters first arrived, save for the rise and fall of the sea levels due to the glaciation of the northern and southern ice caps, which in turn repeatedly exposed and submerged land bridges that allowed hamsters to migrate across continents only to later be isolated from their relatives, to diverge genetically and become a new species.

The climate of the Late Rodentocene is temperate and humid, and conducive to the growth of a wide array of biomes across its six primary continents: small Borealia in the north, Easaterra and Nodera south and east of Borealia, temperate Westerna and tropical Ecatoria across the expanse of the Centralic Ocean, and the oddly-shaped Peninsulaustra at the south of the Centralic. For a brief period spanning a few thousand years, they were all connected when the sea level dropped, bridging them all to Isla Genesis (highlighted in orange), the experimental island where hamsters were first released as test subjects in a secluded environment.

With the land bridges long since sunk, however, the continents have been cut off from one another and in their separation have developed their own unique flora and fauna, such as Peninsulaustra becoming an frigid tundra home to species adapted to the cold, and Borealia, with only a few species making it across the land bridge before it flooded over, now being a thriving hotspot for endemic species found nowhere else on the planet.

The seas are also thriving as of the Late Rodentocene: while no hamsters have colonized it, at least just yet, the warm waters are flourishing with reefs and algae forests that grow with tremendous jungles of kelp that form their own biome from small organisms that take shelter in them. Most conspicuously, however, are the lack of fish: and in the absence of the dominant marine vertebrates of Earth, strange new clades have evolved in the briny depths, to fill the gaps left vacant.

The era is a time of stability: for the next tens of millions of years, the clime and tectonics will change little and the biomes will remain habitable and little-changing. But while the world itself stagnates, its creatures do not -- and this era will be their first big hurrah, as the planet's dominant clade.

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Ain't No Passing Craze: The Great Ecatorian Desert

The continent of Ecatoria is a lush, warm tropical region, fed and nourished by rainfall from the South Ecatorian Sea. But not all of it is drizzled with a constant supply of precipitation: west of the mid-Ecatorian mountain ranges lies an expanse of land shielded from storms and moisture, and thus is dry and arid: the Great Ecatorian Desert, the largest desert on HP-02017 in the Late Rodentocene.

It is a hot afternoon in the Ecatorian Desert, and Alpha shines scorchingly overhead. On the western horizon Beta slowly begins to set, as the two suns are now separated by half a day: the coming of spring. But while elsewhere on Ecatoria spring would be mild and rainy, here in the Ecatorian Desert the climate is scorching in the day and chilling in the night: and despite this conditions some specialized organisms are able to eke out an existence in this inhospitable land.

A dark shadow glides overhead: a predatory ratbat, scouring from the skies above for any small creature down below. Though a rodent, this flying hunter is akin to a hawk, having adapted tremendously keen eyesight to home in on any movement down below on ground level. Down below, there is nothing but an expanse of sand and dry grass for miles, punctuated only by occasional towering plants, somewhat resembling cacti but in truth are highly-derived grass. Even the plants of this seeded world have begun evolving to fit new niches, not merely a green background in a planet of animals, but themselves competitors in the evolutionary race.

The ratbat-of-prey spots movement down below and circles around to zero in on its target. However, it quickly breaks off the hunt and soars off in search for another, easier meal: its rejected quarry is far too big to tackle. A desert-dwelling descendant of the cavybaras, it is nearly the size of its ancestor and simply too large for the ratbat to carry off, and so the predator wisely departs, while the lumbering beast below briefly watches the departing figure in curiosity, gives a huffing snort of confusion, and then proceeds on its way.

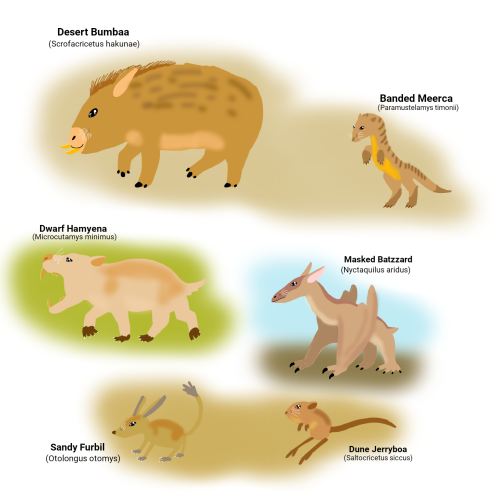

The creature in question is a direct descendant of the cavybaras, that has evolved modified extensions of its lower incisors that grow outward of its mouth, forming tusks which it uses in digging for food and for self-defense. Known as the desert bumbaa (Scrofacricetus hakunae), it is one of the several species of the genus Scrofacricetus, with its other cousins having adapted to different biomes, such as the forest bumbaa (S. matatai) and the plains bumbaa (S. porcius), which thrive in other regions of Ecatoria. The desert bumbaa differes from its cousins by its larger ears and thinner, sparser coat, which helps it lose heat in the arid climate.

The desert bumbaa is an omnivore, feeding mostly on tough shrubs and cacti-analogues in the desert. However, it also greatly relishes insects, many of which nest in burrows or underneath rocks and logs, and so the bumbaa puts its tusks to great use to dig up an abundance of bugs, overturning driftwood and uprooting plants to get at its prize. And its messy eating habits attract the attention of another desert dweller, the banded meerca (Paramustelamys timonii), a small, insectivorous ferrat that has developed a bizarre, and mutualistic, relationship with the bumbaa.

While fond of feasting on bugs, the desert bumbaa itself is plagued by insects of a nastier kind: wingless, bloodsucking flies that have converged with ticks and fleas as external parasites of mammalian hosts. These bugs cause the bumbaa great discomfort, but that is when the meerca comes to the rescue: an avid insectivore, it not only feeds upon the escaping leftovers of bumbaas while they raid insect nests, but also plucks the pests off the bumbaa's thick hide, offering them relief. The bumbaas have learned to tolerate and even welcome their presence, actively seeking them out and laying down to be groomed from parasites, while the meercas follow bumbaas around to be led to insect nests which the bumbaas then dig up, allowing the tiny meercas to share access to a buffet of bugs otherwise out of their reach.

Another benefit the meercas gain from the company of their lumbering companion is protection from predators: and indeed, there is a specialized predator prowling this dessicated wasteland: the dwarf hamyena (Microcutamys minimus). Smaller than many of its other relatives across Ecatoria but no less a deadly hunter, this badger-sized predator is descended from the hammibals of ten million years prior, and specializes on small rodents- including meercas. However, a full-grown bumbaa is too much for them to handle, their sharp tusks potentially being wielded with lethal force: as such, as long as the bumbaas are around, the meercas are safe from their small but fearsome enemy.

Other rodents also thrive in the Ecatorian Desert: furbils and jerryboas, ever present throughout the planet in all their diversity, exist in numerous forms throughout the desert landscape, feeding on insects, seeds and cactus-analogues, which they chew through their tough outer skin to reach the water-rich tissues inside. Their large ears and long tails act as heat sinks to lose excess heat, while their pale fur reflects heat and camouflages them in the light-colored sandy soil.

These tiny rodents, in turn, form a major part of the diet of the desert's primary aerial hunter, the masked batzzard (Nyctaquilus aridus). With a wingspan of about four feet, this desert ratbat circles the daytime sky, seeking out small prey such as jerryboas, furbils and meercas, which it swoops down onto, pounces on with its wing claws, and dispatches with a bite from its sharp, stabbing incisors. Hooked talons on its forelimbs ensure that prey is unable to easily escape, attacking its targets with an unusual hunting strike partly like a hawk, and partly like a cat. While live bumbaas are far too big to deal with, dead ones certainly aren't off the menu, and groups of batzzards may occasionally congregate at a carcass, where, due to their normally solitary lifestyle, nearly all their social interaction takes place, such as courtship, mating and dominance posturing.

Even in this harsh, dry landscape, life on HP-02017 has found a way. A wide, diverse collection of life thrives in this barren wilderness, despite its challenges --competing, coexisting, and even cooperating with one another, to overcome the harsh and unforgiving trials of life in the Great Ecatorian Desert.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

All art is derivative. Yes, there should be protections of the rights of artists that their work can't be used in databases of AI art without consent. And yes AI does not consciously create art. In that sense, it is a tool for creating art. I don't see why these things make AI art inherently wrong or anyone using them wrong. By the way, I have only ever shared AI art with a small number of friends and only from programs I trust to be using public domain datasets You shouldn't paint everyone using AI for art with the same brush.

AI Art and Why It Can Go Die In A Fire

Why am I opposed to Stable Diffusion and AI Art in its current incarnation:

Some people seem to believe AI can “learn” art. Like it learns the concepts of perspective, value, anatomy, colour etc. through images and then recreates art based on this knowledge.

This is a misconception.

An AI doesn’t “know” things. It has no concept for artistic fundamentals. It just learns associations based on the data it’s given in a way that’s completely , vastly different to the way a human brain does. An AI can only recreate based on known image data. Those recreations can be blended in a very complex way, but they will ALWAYS be derived directly from image data it’s trained on.

A human can take a paint-bucket, and throw it at a canvas, and then mush paint around with their fingers. An AI can’t do that; it can only blend image data that best fits “canvas with messy splashed paint”. It will pull from all the image data it’s categorized with “canvas”, “splash”, “paint”, etc. and then blend them by placing datapoints next to other datapoints that it has “learned” will most suitably go next to each other.

Human learning creates complex conceptual structures. Our concept of an “apple” may contain many elements such as the colour red, how heavy it is, its overall form, how you hold it, and what it tastes like. An AI’s concept of an “apple” is whatever images it associates with the word “apple” based on text cues in its training.

When you tell it to paint “a hand holding an apple”, it will recreate and blend many images of hands with many images of apples in a way that best fit each other depending on weights defined by the data its analyzed.

Any presumption that AI can “learn” art theory and then make art through its knowledge of this is incorrect, and would require a level of general AI intelligence we are nowhere near capable of building yet, and we won’t with our current models because they are not creating actual epistemology, merely datapoint-based imitation without actual integration or understanding.

But the bottom line? All AI art is derivative and, unless it was trained exclusively on works in the public domain, there is definitely a case to argue that the companies creating these algorithms are violating the copyright of the artists whose works they are using without there first being a contract, agreement, or royalties (which is the thing these companies are trying to weasel out of by creating these AIs in the first place.) There is a reason why Clip Studio Paint, the latest of money-chasers jumping aboard the Stable Diffusion pony, issued out a warning that states, verbatim, “we cannot guarantee that images generated by the current model will not infringe on the rights of others.“

They know. They just don’t care- and everyone who ‘creates’ AI art is a willing participant in the infringing of copyright of millions of artists who never gave consent to have their works used in this fashion.

-

sizzlingyourfakeids liked this · 1 month ago

sizzlingyourfakeids liked this · 1 month ago -

u531355an0ma1y liked this · 1 month ago

u531355an0ma1y liked this · 1 month ago -

justahumanmessingaround liked this · 1 month ago

justahumanmessingaround liked this · 1 month ago -

kedterblog liked this · 1 month ago

kedterblog liked this · 1 month ago -

applesaucesea liked this · 1 month ago

applesaucesea liked this · 1 month ago -

timeless-titan liked this · 1 month ago

timeless-titan liked this · 1 month ago -

icecoffeemylove liked this · 1 month ago

icecoffeemylove liked this · 1 month ago -

meimeiwatson liked this · 1 month ago

meimeiwatson liked this · 1 month ago -

eleanorandphantom liked this · 2 months ago

eleanorandphantom liked this · 2 months ago -

starlantern liked this · 2 months ago

starlantern liked this · 2 months ago -

writer-fennec liked this · 2 months ago

writer-fennec liked this · 2 months ago -

halloghost liked this · 2 months ago

halloghost liked this · 2 months ago -

xsea-beex liked this · 2 months ago

xsea-beex liked this · 2 months ago -

herefordamaymays liked this · 2 months ago

herefordamaymays liked this · 2 months ago -

orb-posting-zone liked this · 2 months ago

orb-posting-zone liked this · 2 months ago -

unfunnymeme liked this · 3 months ago

unfunnymeme liked this · 3 months ago -

lonewanderer-lostsoul liked this · 3 months ago

lonewanderer-lostsoul liked this · 3 months ago -

eluxurex liked this · 3 months ago

eluxurex liked this · 3 months ago -

wis3-owl liked this · 3 months ago

wis3-owl liked this · 3 months ago -

lanigironu liked this · 3 months ago

lanigironu liked this · 3 months ago -

thedevildoesdrvgs liked this · 3 months ago

thedevildoesdrvgs liked this · 3 months ago -

starg1rl4ever liked this · 3 months ago

starg1rl4ever liked this · 3 months ago -

mia-cot liked this · 3 months ago

mia-cot liked this · 3 months ago -

sphericalbee liked this · 3 months ago

sphericalbee liked this · 3 months ago -

smellyboy-32 liked this · 4 months ago

smellyboy-32 liked this · 4 months ago -

the-unknown-fandom liked this · 4 months ago

the-unknown-fandom liked this · 4 months ago -

justhereformemes999 liked this · 4 months ago

justhereformemes999 liked this · 4 months ago -

httpsastral liked this · 4 months ago

httpsastral liked this · 4 months ago -

30-fucking-boiled-potatoes liked this · 4 months ago

30-fucking-boiled-potatoes liked this · 4 months ago -

lyrelunamoon liked this · 4 months ago

lyrelunamoon liked this · 4 months ago -

gamblingwithmyssoul liked this · 4 months ago

gamblingwithmyssoul liked this · 4 months ago -

prettyprettypretttyalien liked this · 4 months ago

prettyprettypretttyalien liked this · 4 months ago -

lettersnbersanddashes liked this · 4 months ago

lettersnbersanddashes liked this · 4 months ago -

yviisxo liked this · 4 months ago

yviisxo liked this · 4 months ago -

kookies-and-kream07 liked this · 4 months ago

kookies-and-kream07 liked this · 4 months ago -

laczm0cy liked this · 4 months ago

laczm0cy liked this · 4 months ago -

xiaos--wifeyy liked this · 4 months ago

xiaos--wifeyy liked this · 4 months ago -

huntersulamaka liked this · 5 months ago

huntersulamaka liked this · 5 months ago -

theres-rue-for-you liked this · 5 months ago

theres-rue-for-you liked this · 5 months ago -

killed-by-gnomes liked this · 5 months ago

killed-by-gnomes liked this · 5 months ago -

supernaturalloverdestiel liked this · 5 months ago

supernaturalloverdestiel liked this · 5 months ago -

tape-dragon liked this · 5 months ago

tape-dragon liked this · 5 months ago -

cypress404 liked this · 5 months ago

cypress404 liked this · 5 months ago -

frutiestorange liked this · 5 months ago

frutiestorange liked this · 5 months ago -

geekynerdydorkyme liked this · 5 months ago

geekynerdydorkyme liked this · 5 months ago