All Cats Are Beautiful

All Cats Are Beautiful

More Posts from Ocrim1967 and Others

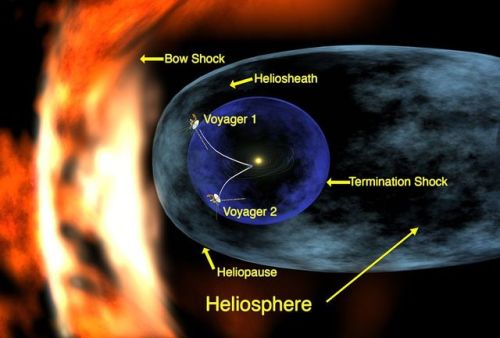

The heliosphere is the bubble-like region of space dominated by the Sun, which extends far beyond the orbit of Pluto. Plasma “blown” out from the Sun, known as the solar wind, creates and maintains this bubble against the outside pressure of the interstellar medium, the hydrogen and helium gas that permeates the Milky Way Galaxy. The solar wind flows outward from the Sun until encountering the termination shock, where motion slows abruptly. The Voyager spacecraft have explored the outer reaches of the heliosphere, passing through the shock and entering the heliosheath, a transitional region which is in turn bounded by the outermost edge of the heliosphere, called the heliopause. The shape of the heliosphere is controlled by the interstellar medium through which it is traveling, as well as the Sun and is not perfectly spherical. The limited data available and unexplored nature of these structures have resulted in many theories. The word “heliosphere” is said to have been coined by Alexander J. Dessler, who is credited with first use of the word in the scientific literature.

On September 12, 2013, NASA announced that Voyager 1 left the heliopause on August 25, 2012, when it measured a sudden increase in plasma density of about forty times. Because the heliopause marks one boundary between the Sun’s solar wind and the rest of the galaxy, a spacecraft such as Voyager 1 which has departed the heliosphere, can be said to have reached interstellar space. source

Lunar eclipse 2019

Image credit: Dan Wery

Hilarious Animal Snapchats That Are Impossible Not To Laugh At

Black holes

A black hole is a region of spacetime exhibiting such strong gravitational effects that nothing—not even particles and electromagnetic radiation such as light—can escape from inside it. The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass can deform spacetime to form a black hole. The boundary of the region from which no escape is possible is called the event horizon. Although the event horizon has an enormous effect on the fate and circumstances of an object crossing it, no locally detectable features appear to be observed. In many ways a black hole acts like an ideal black body, as it reflects no light.

The idea of a body so massive that even light could not escape was briefly proposed by astronomical pioneer and English clergyman John Michell in a letter published in November 1784. Michell’s simplistic calculations assumed that such a body might have the same density as the Sun, and concluded that such a body would form when a star’s diameter exceeds the Sun’s by a factor of 500, and the surface escape velocity exceeds the usual speed of light.

At the center of a black hole, as described by general relativity, lies a gravitational singularity, a region where the spacetime curvature becomes infinite. For a non-rotating black hole, this region takes the shape of a single point and for a rotating black hole, it is smeared out to form a ring singularity that lies in the plane of rotation. In both cases, the singular region has zero volume. It can also be shown that the singular region contains all the mass of the black hole solution. The singular region can thus be thought of as having infinite density.

How Do Black Holes Form?

Scientists think the smallest black holes formed when the universe began.

Stellar black holes are made when the center of a very big star falls in upon itself, or collapses. When this happens, it causes a supernova. A supernova is an exploding star that blasts part of the star into space.

Scientists think supermassive black holes were made at the same time as the galaxy they are in.

Supermassive black holes, which can have a mass equivalent to billions of suns, likely exist in the centers of most galaxies, including our own galaxy, the Milky Way. We don’t know exactly how supermassive black holes form, but it’s likely that they’re a byproduct of galaxy formation. Because of their location in the centers of galaxies, close to many tightly packed stars and gas clouds, supermassive black holes continue to grow on a steady diet of matter.

If Black Holes Are “Black,” How Do Scientists Know They Are There?

A black hole can not be seen because strong gravity pulls all of the light into the middle of the black hole. But scientists can see how the strong gravity affects the stars and gas around the black hole.

Scientists can study stars to find out if they are flying around, or orbiting, a black hole.

When a black hole and a star are close together, high-energy light is made. This kind of light can not be seen with human eyes. Scientists use satellites and telescopes in space to see the high-energy light.

On 11 February 2016, the LIGO collaboration announced the first observation of gravitational waves; because these waves were generated from a black hole merger it was the first ever direct detection of a binary black hole merger. On 15 June 2016, a second detection of a gravitational wave event from colliding black holes was announced.

Simulation of gravitational lensing by a black hole, which distorts the image of a galaxy in the background

Animated simulation of gravitational lensing caused by a black hole going past a background galaxy. A secondary image of the galaxy can be seen within the black hole Einstein ring on the opposite direction of that of the galaxy. The secondary image grows (remaining within the Einstein ring) as the primary image approaches the black hole. The surface brightness of the two images remains constant, but their angular size varies, hence producing an amplification of the galaxy luminosity as seen from a distant observer. The maximum amplification occurs when the background galaxy (or in the present case a bright part of it) is exactly behind the black hole.

Could a Black Hole Destroy Earth?

Black holes do not go around in space eating stars, moons and planets. Earth will not fall into a black hole because no black hole is close enough to the solar system for Earth to do that.

Even if a black hole the same mass as the sun were to take the place of the sun, Earth still would not fall in. The black hole would have the same gravity as the sun. Earth and the other planets would orbit the black hole as they orbit the sun now.

The sun will never turn into a black hole. The sun is not a big enough star to make a black hole.

More posts about black holes

Source 1, 2 & 3

Hurricanes Have No Place to Hide, Thanks to Better Satellite Forecasts

If you’ve ever looked at a hurricane forecast, you’re probably familiar with “cones of uncertainty,” the funnel-shaped maps showing a hurricane’s predicted path. Thirty years ago, a hurricane forecast five days before it made landfall might have a cone of uncertainty covering most of the East Coast. The result? A great deal of uncertainty about who should evacuate, where it was safe to go, and where to station emergency responders and their equipment.

Over the years, hurricane forecasters have succeeded in shrinking the cone of uncertainty for hurricane tracks, with the help of data from satellites. Polar-orbiting satellites, which fly nearly directly above the North and South Poles, are especially important in helping cut down on forecast error.

The orbiting electronic eyeballs key to these improvements: the Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) fleet. A collaborative effort between NOAA and NASA, the satellites circle Earth, taking crucial measurements that inform the global, regional and specialized forecast models that have been so critical to hurricane track forecasts.

The forecast successes keep rolling in. From Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria in 2017 through Hurricanes Florence and Michael in 2018, improved forecasts helped manage coastlines, which translated into countless lives and property saved. In September 2018, with the help of this data, forecasters knew a week ahead of time where and when Hurricane Florence would hit. Early warnings were precise enough that emergency planners could order evacuations in time — with minimal road clogging. The evacuations that did not have to take place, where residents remained safe from the hurricane’s fury, were equally valuable.

The satellite benefits come even after the storms make landfall. Using satellite data, scientists and forecasters monitor flooding and even power outages. Satellite imagery helped track power outages in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria and in the Key West area after Hurricane Irma, which gave relief workers information about where the power grid was restored – and which regions still lacked electricity.

Flood maps showed the huge extent of flooding from Hurricane Harvey and were used for weeks after the storm to monitor changes and speed up recovery decisions and the deployment of aid and relief teams.

As the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season kicks off, the JPSS satellites, NOAA-20 and Suomi-NPP, are ready to track hurricanes and tropical cyclones as they form, intensify and travel across the ocean – our eyes in the sky for severe storms.

For more about JPSS, follow @JPSSProgram on Twitter and facebook.com/JPSS.Program, or @NOAASatellites on Twitter and facebook.com/NOAASatellites.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Earth: Our Oasis in Space

Earth: It’s our oasis in space, the one place we know that harbors life. That makes it a weird place – so far, we haven’t found life anywhere else in the solar system…or beyond. We study our home planet and its delicate balance of water, atmosphere and comfortable temperatures from space, the air, the ocean and the ground.

To celebrate our home, we want to see what you love about our planet. Share a picture, or several, of Earth with #PictureEarth on social media. In return, we’ll share some of our best views of our home, like this one taken from a million miles away by the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (yes, it’s EPIC).

From a DC-8 research plane flying just 1500 feet above Antarctic sea ice, we saw a massive iceberg newly calved off Pine Island Glacier. This is one in a series of large icebergs Pine Island has lost in the last few years – the glacier is one of the fastest melting in Antarctica.

It’s not just planes. We also saw the giant iceberg, known as B-46, from space. Landsat 8 tracked B-46’s progress after it broke off from Pine Island Glacier and began the journey northward, where it began to break apart and melt into the ocean.

Speaking of change, we’ve been launching Earth-observing satellites since 1958. In that time, we’ve seen some major changes. Cutting through soft, sandy soil on its journey to the Bay of Bengal, the Padma River in Bangladesh dances across the landscape in this time-lapse of 30 years’ worth of Landsat images.

Our space-based view of Earth helps us track other natural activities, too. With both a daytime and nighttime view, the Aqua satellite and the Suomi NPP satellite helped us see where wildfires were burning in California, while also tracking burn scars and smoke plumes..

Astronauts have an out-of-this-world view of Earth, literally. A camera mounted on the International Space Station captured this image of Hurricane Florence after it intensified to Category 4.

It’s not just missions studying Earth that capture views of our home planet. Parker Solar Probe turned back and looked at our home planet while en route to the Sun. Earth is the bright, round object.

Want to learn more about our home planet? Check out our third episode of NASA Science Live where we talked about Earth and what makes it so weird.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

Unusual Signal Suggests Neutron Star Destroyed by Black Hole

What created this unusual explosion? Three weeks ago, gravitational wave detectors in the USA and Europe – the LIGO and Virgo detectors – detected a burst of gravitational radiation that had the oscillating pattern expected when a black hole destroys a neutron star. One object in event S190814sv was best fit with a mass greater than five times the mass of the Sun – making it a good candidate for a black hole, while the other object appeared to have a mass less than three times the mass of the Sun – making it a good candidate for a neutron star. No similar event had been detected with gravitational waves before. Unfortunately, no light was seen from this explosion, light that might have been triggered by the disrupting neutron star. It is theoretically possible that the lower mass object was also a black hole, even though no clear example of a black hole with such a low mass is known. The featured video was created to illustrate a previously suspected black hole - neutron star collision detected in light in 2005, specifically gamma-rays from the burst GRB 050724. The animated video starts with a foreground neutron star orbiting a black hole surrounded by an accretion disk. The black hole’s gravity then shreds the neutron star, creating a jet as debris falls into the black hole. S190814sv will continue to be researched, with clues about the nature of the objects involved possibly coming from future detections of similar systems. Illustration Video Credit: NASA, Dana Berry (Skyworks Digital)

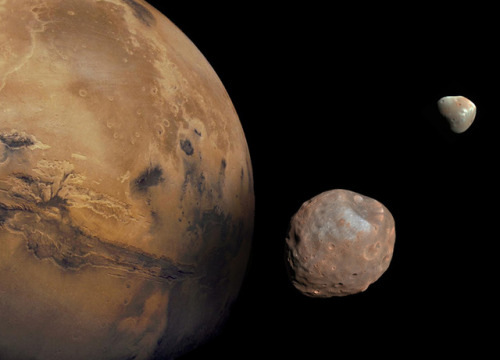

In 40 million years, Mars may have a ring (and one fewer moon)

Nothing lasts forever - especially Phobos, one of the two small moons orbiting Mars. The moonlet is spiraling closer and closer to the Red Planet on its way toward an inevitable collision with its host. But a new study suggests that pieces of Phobos will get a second life as a ring around the rocky planet.

A moon - or moonlet - in orbit around a planet has three possible destinies. If it is just the right distance from its host, it will stay in orbit indefinitely. If it’s beyond that point of equilibrium, it will slowly drift away. (This is the situation with the moon; as it gradually pulls away from Earth, its orbit is growing by about 1.5 inches per year.) And if a moon starts out on the too-close side, its orbit will keep shrinking until there is no distance left between it and its host planet. The Martian ring will last for at least 1 million years - and perhaps for as long as 100 million years, according to the study.

The rest of Phobos will probably remain intact, until it hits the Martian surface. But it won’t be a direct impact; instead, the moonlet’s remains will strike at an oblique angle, skipping along the surface like a smooth stone on a calm lake.

This has probably happened before - scientists believe a group of elliptical craters on the Martian surface were caused by a small moon that skidded to its demise. (If this were to happen on Earth, our planet’s greater mass would produce a crash as big as the one that wiped out the dinosaurs, the researchers noted as an aside.)

source

images: NASA/JPL, Tushar Mittal using Celestia 2001-2010, Celestia Development Team.

-

fonfon1888 liked this · 6 months ago

fonfon1888 liked this · 6 months ago -

alfaman88 liked this · 7 months ago

alfaman88 liked this · 7 months ago -

annita89e5qypoh liked this · 7 months ago

annita89e5qypoh liked this · 7 months ago -

dorotheasbyotch liked this · 8 months ago

dorotheasbyotch liked this · 8 months ago -

nilusanimationworld liked this · 8 months ago

nilusanimationworld liked this · 8 months ago -

abysmallylost23 reblogged this · 11 months ago

abysmallylost23 reblogged this · 11 months ago -

koronbain-tenshidere reblogged this · 1 year ago

koronbain-tenshidere reblogged this · 1 year ago -

alerpromarin liked this · 1 year ago

alerpromarin liked this · 1 year ago -

gangsandxakoufat liked this · 1 year ago

gangsandxakoufat liked this · 1 year ago -

matchmabheaddwebdi liked this · 1 year ago

matchmabheaddwebdi liked this · 1 year ago -

future-newswire liked this · 1 year ago

future-newswire liked this · 1 year ago -

tioprecenbi liked this · 1 year ago

tioprecenbi liked this · 1 year ago -

anmarfaihur liked this · 1 year ago

anmarfaihur liked this · 1 year ago -

basspinanmo liked this · 1 year ago

basspinanmo liked this · 1 year ago -

althemadindian liked this · 1 year ago

althemadindian liked this · 1 year ago -

ama-mori liked this · 2 years ago

ama-mori liked this · 2 years ago