Happy Almost Birthday, Shakespeare! Or Should I Say Bard-thday? Recently, In Honour Of The 400th Anniversary

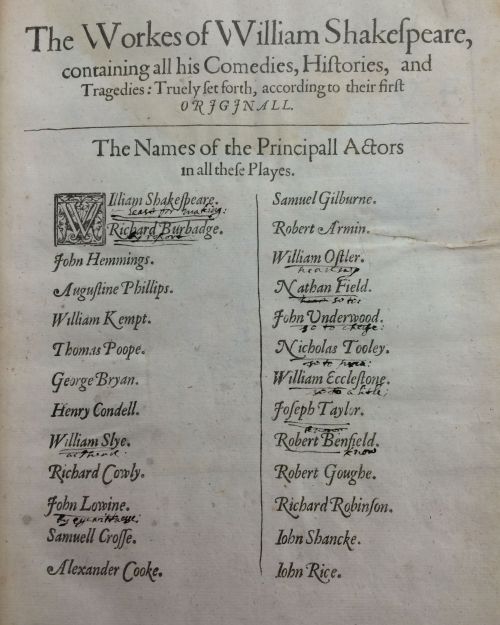

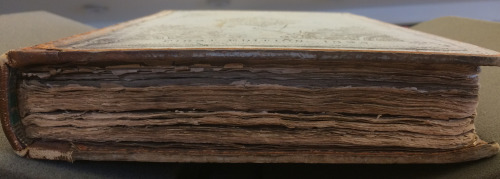

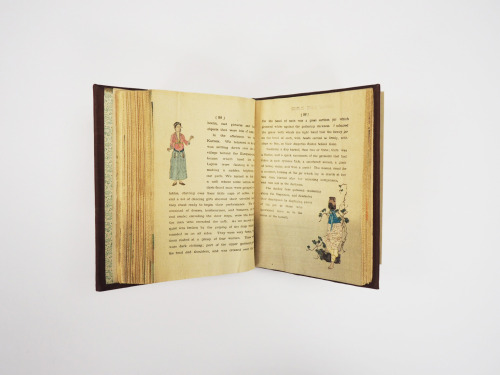

Happy almost birthday, Shakespeare! Or should I say Bard-thday? Recently, in honour of the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death (conveniently for celebratory purposes, he was born on April 23 1564 and died on the same day in 1616), I was given the incredible opportunity to have a private audience to go through the University of Glasgow’s copy of the First Folio, page by page. I’ve written a short article for the University Library’s blog, which you can find here, but I wanted to share some other images on my own blog that I didn’t have room for on the official post!

The University of Glasgow’s First Folio (more properly known as Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies) is able to tell so many more stories than those of the plays contained in its pages- of the history of the antiquarian book trade, of the printing practices of the Renaissance, of book ownership and value. Rest assured, you’ll probably be seeing posts from me in the future about all of these things, as well as the typographical ornaments used in the book, which I found fascinating. The University’s Folio is particularly interesting due to the notations by past owners, including one who had apparently seen at least one of the original Chamberlain’s Men “By eyewittnesse”. But my favourite bit of the later additions is the morbid little poem on the reverse of one of the flyleaves: “Pitty it is the fam’d Shakespeare/ Shall ever want his chin or haire.”

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

How many did you know? All worth reading more about!!

11 New Facts Science Has Revealed About The Body

1. Hundreds of genes spring to life after you die - and they keep functioning for up to four days.

2. Livers grow by almost half during waking hours.

3. The root cause of eczema has finally been identified.

4. We were wrong - the testes are connected to the immune system after all.

5. The causes of hair loss and greying are linked, and for the first time, scientists have identified the cells responsible.

6. A brand new human organ has been classified - the mesentery - an organ that’s been hiding in plain sight in our digestive system this whole time.

7. An unexpected new lung function has been found - they also play a key role in blood production, with the ability to produce more than 10 million platelets (tiny blood cells) per hour.

8. Your appendix might actually be serving an important biological function- and one that our species isn’t ready to give up just yet.

9. The brain literally starts eating itself when it doesn’t get enough sleep. brain to clear a huge amount of neurons and synaptic connections away.

10. Neuroscientists have discovered a whole new role for the brain’s cerebellum - it could actually play a key role in shaping human behaviour.

11. Our gut bacteria are messing with us in ways we could never have imagined. Neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s might actually start out in the gut, rather than the brain, and there’s mounting evidence that the human microbiome could be to blame for chronic fatigue syndrome.

(Image caption: Measurement of brain activity in a patient with phantom limb pain. Credit: Osaka University)

Cause of phantom limb pain in amputees, and potential treatment, identified

Researchers have discovered that a ‘reorganisation’ of the wiring of the brain is the underlying cause of phantom limb pain, which occurs in the vast majority of individuals who have had limbs amputated, and a potential method of treating it which uses artificial intelligence techniques.

The researchers, led by a group from Osaka University in Japan in collaboration with the University of Cambridge, used a brain-machine interface to train a group of ten individuals to control a robotic arm with their brains. They found that if a patient tried to control the prosthetic by associating the movement with their missing arm, it increased their pain, but training them to associate the movement of the prosthetic with the unaffected hand decreased their pain.

Their results, reported in the journal Nature Communications, demonstrate that in patients with chronic pain associated with amputation or nerve injury, there are ‘crossed wires’ in the part of the brain associated with sensation and movement, and that by mending that disruption, the pain can be treated. The findings could also be applied to those with other forms of chronic pain, including pain due to arthritis.

Approximately 5,000 amputations are carried out in the UK every year, and those with type 1 or type 2 diabetes are at particular risk of needing an amputation. In most cases, individuals who have had a hand or arm amputated, or who have had severe nerve injuries which result in a loss of sensation in their hand, continue to feel the existence of the affected hand as if it were still there. Between 50 and 80 percent of these patients suffer with chronic pain in the ‘phantom’ hand, known as phantom limb pain.

“Even though the hand is gone, people with phantom limb pain still feel like there’s a hand there – it basically feels painful, like a burning or hypersensitive type of pain, and conventional painkillers are ineffective in treating it,” said study co-author Dr Ben Seymour, a neuroscientist based in Cambridge’s Department of Engineering. “We wanted to see if we could come up with an engineering-based treatment as opposed to a drug-based treatment.”

A popular theory of the cause of phantom limb pain is faulty ‘wiring’ of the sensorimotor cortex, the part of the brain that is responsible for processing sensory inputs and executing movements. In other words, there is a mismatch between a movement and the perception of that movement.

In the study, Seymour and his colleagues, led by Takufumi Yanagisawa from Osaka University, used a brain-machine interface to decode the neural activity of the mental action needed for a patient to move their ‘phantom’ hand, and then converted the decoded phantom hand movement into that of a robotic neuroprosthetic using artificial intelligence techniques.

“We found that the better their affected side of the brain got at using the robotic arm, the worse their pain got,” said Yanagisawa. “The movement part of the brain is working fine, but they are not getting sensory feedback – there’s a discrepancy there.”

The researchers then altered their technique to train the ‘wrong’ side of the brain: for example, a patient who was missing their left arm was trained to move the prosthetic arm by decoding movements associated with their right arm, or vice versa. When they were trained in this counter-intuitive technique, the patients found that their pain significantly decreased. As they learned to control the arm in this way, it takes advantage of the plasticity – the ability of the brain to restructure and learn new things – of the sensorimotor cortex, showing a clear link between plasticity and pain.

Although the results are promising, Seymour warns that the effects are temporary, and require a large, expensive piece of medical equipment to be effective. However, he believes that a treatment based on their technique could be available within five to ten years. “Ideally, we’d like to see something that people could have at home, or that they could incorporate with physio treatments,” he said. “But the results demonstrate that combining AI techniques with new technologies is a promising avenue for treating pain, and an important area for future UK-Japan research collaboration.”

A whole lot of books

In 1610, after successfully rebuilding, reopening and firmly establishing the Bodleian Library, Sir Thomas Bodley made it his new goal to ensure the library’s long-term relevance. He forged an agreement with the Stationers’ Company that saw his library receive one copy of everything printed under royal license. This would guarantee that the Bodleian would continue to be at the cutting edge of literature and librarianship.

And this was when the Bodleian became, by effect, the first Legal Deposit library in the UK. From 1662, the notions were solidified and the Royal Library and the University Library of Cambridge were also party to the same privileges. Until the establishment of the British Library in 1753, the university libraries of Oxford and Cambridge - especially the Bodleian Library, which had enjoyed the legal deposit privilege the longest – served as the de facto national libraries of the United Kingdom.

But what’s the current state of Legal Deposit at the Bodleian? And, as @LowlandsLady asked us on Twitter, might it ever feel like a curse to have this multitude of books rolling into the library?

There’s nobody better to answer these questions than Jackie Raw, Head of Legal Deposit Operations in our Collections Management department. From this point on, this Tumblr post belongs to Jackie.

The Legal Deposit Libraries Act 2003 obliges publishers to deposit, at their own cost, one copy of every printed publication that is published or distributed in the UK with the British Library and, upon request, with up to five other Legal Deposit Libraries of which the Bodleian is one.

These Legal Deposit Libraries seek to ensure that the UK published output is preserved for posterity. To do this the requesting libraries together use the Agency for the Legal Deposit Libraries. The Agency makes claims for titles on our behalf and, on receipt, these are recorded and distributed weekly to the libraries. By collaborating the Legal Deposit Libraries seek to develop and co-ordinate national coverage and preservation of, and access to, publications acquired by legal deposit.

A random selection of books arriving by Legal Deposit.

While the Legal Deposit system has existed in various forms since 1662, the reformed Act in 2003 extended the provision for printed material to cover non-print works. This brings new and emerging publishing media under its scope. The Regulations for this came into force in April 2013. We now have the opportunity to add e-books, e-journals, digital maps and digital music scores to our collections and to harvest and archive content from UK-published material on UK websites under the new legislation.

Again the libraries are working together to ensure coverage. The benefits of holding a collection of over 12 million physical items, much of which has been deposited under Legal Deposit, and a growing digital collection cannot be overstated.

A recent count of books arriving daily at the Bodleian Libraries.

Legal Deposit ensures the nation’s heritage is collected systematically and preserved for posterity. It supports and advances the teaching and research activities of the University of Oxford and national and international scholarship more widely by collecting, recording and making available this material and it provides, in a cost-effective way, access to a wide range of publications many of which are unlikely to be found outside of the Legal Deposit system.

However, it is also a responsibility.

Clearly there can be pressures on space, storage and transportation. There are staff levels and processing costs to consider and issues around funding limitations. On the other hand there is provision within the Act to allow libraries, other than the British Library, to be selective in what we acquire. So, by consulting and collaborating we aim to ensure as complete coverage as possible within resourcing limits without overburdening any one library with the rate at which our collections are growing.

David Bowie (1947-2016) at Kyoto - Japan - 1980

Photos by Sukita Masayoshi 鋤田 正義

Ancient Egypt as seen through western eyes is mostly monumental and remote, distant in time and overwhelming in scale. The earliest western illustrations and photographs of Egypt regularly emphasized size and stillness; romantic artists of the nineteenth century frequently placed people in vast desert landscapes—the figures small and insignificant, lost in the deep antiquity of an unchanging land.

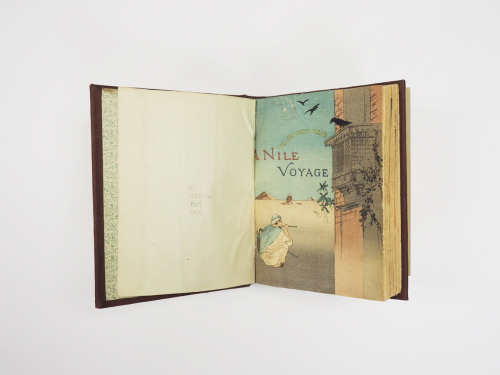

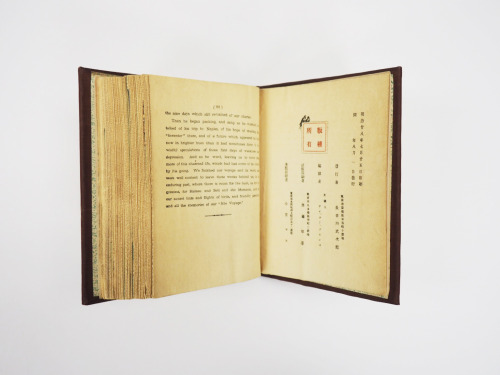

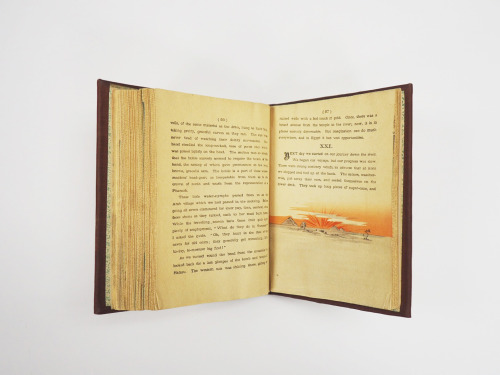

This grand vision of Egypt is so firmly fixed in western culture that discovering a different interpretation comes as a revelation. Fortunately, the Brooklyn Museum Wilbour Library of Egyptology owns a rare treasure that offers an alternate view. A Nile Voyage of Recovery, by Charles and Susan Bowles was published in Japan by Hasegawa Takejirō [長谷川武次郎 in 1896. Hasegawa was Japanese publisher active in the late nineteenth century who specialized in books in European languages, often for Japan’s tourist trade and resident foreign community, which included many English missionaries. The volume is part of the Red Cross series. During this time period, the Red Cross was active in setting up libraries and creating publications for soldiers in hospitals and recovery centers around the world.

Many of Hasegawa’s early books were in the form of chirimen-bon (ちりめん本) or crêpe paper books. Chirimen, or crepe, is a Japanese textile with a soft, slightly wrinkly texture that’s often used in Japan to make kimonos, or for wrapping cloth. Hasegawa used the material to produce small, delicate books that can be held in the hand with the pages unfolding easily like fabric.

Our chirimen-bon of A Nile Voyage of Recovery is illustrated with graceful, color woodblock prints of Egyptian scenes and adorned with exquisite typography. The images are gentle and intimate, emphasizing details and delicate color. Even a portrayal of the great pyramid gives more page-room to rays of light and the sun rather than the monuments. The Sphinx does not dominate; it’s rather an integral part of the landscape.

Why study this human-scale Egypt? Because the purpose of art after all is to unsettle the conventional view—and whenever we see the world through other eyes, we see something new.

Posted by Roberta Munoz Photos by Brooke Baldeschwiler

The @unirdg-collections Squint

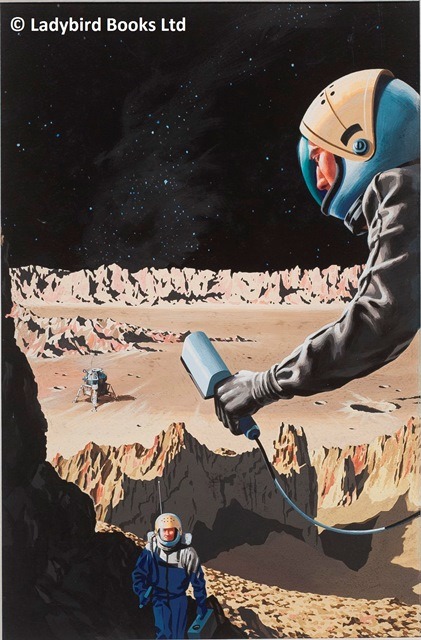

The University of Reading holds the archive of original artwork for the much-loved Ladybird children’s book. This painting on board was used to illustrate Exploring Space, a Ladybird ‘Achievements’ Book first published in 1964. The artwork was created by Brian Knight.

If you look closely at the painting, you can see the faint trace of Knight’s initial design for the lunar landing module - just visible under the later amendment.

Published before the first Moon landing in 1969, the fantasy spacecraft was sleek and utopian. It typifies the extent to which The Space Race captured our mid-century imaginations and permeated visual culture. The later correction, based on the Eagle Lunar Module, was printed in subsequent revisions to the book. It was an acknowledgment of a successful mission and testament to Ladybird’s emphasis on accuracy for its young readers.

All artwork is © Ladybird Books Ltd.

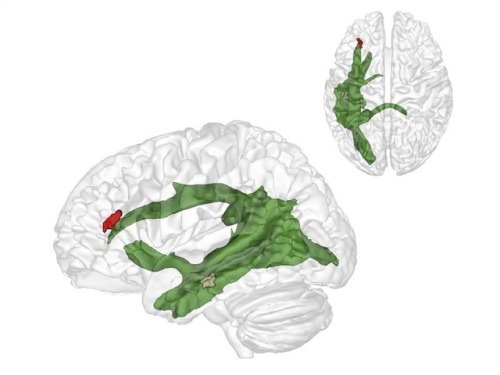

(Image caption: The maturation of fibres of a brain structure called the arcuate fascicle (green) between the ages of three and four years establishes a connection between two critical brain regions: a region (brown) at the back of the temporal lobe that supports adults thinking about others and their thoughts, and a region (red) in the frontal lobe that is involved in keeping things at different levels of abstraction and, therefore, helps us to understand what the real world is and what the thoughts of others are. Credit: © MPI CBS)

The importance of relating to others: why we only learn to understand other people after the age of four

When we are around four years old we suddenly start to understand that other people think and that their view of the world is often different from our own. Researchers in Leiden and Leipzig have explored how that works. Publication in Nature Communications on 21 March.

At around the age of four we suddenly do what three-year-olds are unable to do: put ourselves in someone else’s shoes. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences (MPI CBS) in Leipzig and at Leiden University have shown how this enormous developmental step occurs: a critical fibre connection in the brain matures. Senior researcher and Leiden developmental psychologist Nikolaus Steinbeis, co-author of the article, took part in the research. Lead author, PhD candidate Charlotte Grosse-Wiesmann, worked under his supervision.

Little Maxi

If you tell a 3-year-old child the following story of little Maxi, they will most probably not understand: Maxi puts his chocolate on the kitchen table, then goes to play outside. While he is gone, his mother puts the chocolate in the cupboard. Where will Maxi look for his chocolate when he comes back? A 3-year-old child will not understand why Maxi would be surprised not to find the chocolate on the table where he left it. It is only by the age of 4 years that a child will correctly predict that Maxi will look for his chocolate where he left it and not in the cupboard where it is now.

Theory of Mind

The researchers observed something similar when they showed a 3-year-old child a chocolate box that contained pencils instead of chocolates. When the child was asked what another child would expect to be in the box, they answered “pencils”, although the other child would not know this. Only a year later, around the age of four years, however, will they understand that the other child had hoped for chocolates. Thus, there is a crucial developmental breakthrough between three and four years: this is when we start to attribute thoughts and beliefs to others and to understand that their beliefs can be different from ours. Before that age, thoughts don’t seem to exist independently of what we see and know about the world. That is, this is when we develop a Theory of Mind.

Independent development

The researchers have now discovered what is behind this breakthrough. The maturation of fibres of a brain structure called the arcuate fascicle between the ages of three and four years establishes a connection between two critical brain regions: a region at the back of the temporal lobe that supports adult thinking about others and their thoughts, and a region in the frontal lobe that is involved in keeping things at different levels of abstraction and, therefore, helps us to understand what the real world is and what the thoughts of others are. Only when these two brain regions are connected through the arcuate fascicle can children start to understand what other people think. This is what allows us to predict where Maxi will look for his chocolate. Interestingly, this new connection in the brain supports this ability independently of other cognitive abilities, such as intelligence, language ability or impulse control.

I made this to put on my wall for revision, but I thought it might be helpful for some of you guys too so I thought I would share it!

12 Amazing Facts About Elephants

In honor of World Elephant Day, we present you with 12 little known facts about one of our favorite creatures…in GIFs, of course.

1. Elephants know every member of their herd and are able to recognize up to 30 companions by sight or smell.

2. They can remember and distinguish particular cues that signal danger and can recall locations long after their last visit.

3. An elephant’s memory is not limited to its herd, nor is it limited to its species. In one instance, two circus elephants that performed together rejoiced when crossing paths 23 years later. Elephants have also recognized humans that they once bonded with after decades apart. 4.

4. The elephant boasts the largest brain of any land mammal as well as an impressive encephalization quotient (the size of the animal’s brain relative to its body size). The elephant’s EQ is nearly as high as a chimpanzee’s.

5. The elephant brain is remarkably similar to the human brain, with as many neurons and synapses, as well as a highly developed hippocampus and cerebral cortex.

6. Elephants are one of the few non-human animals to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

7. Elephants are creative problem solvers.

8. Don’t try to outsmart an elephant! They have an understanding of basic arithmetic and can even keep track of relative quantities.

9. Elephants communicate using everything from body signals to infrared rumbles that can be heard from kilometers away. Their understanding of syntax suggests that they have their own language and grammar.

10. Elephants can recognize 12 distinct tones of music and recreate melodies.

11. Elephants are the only non-human animals to mourn their dead, performing burial rituals and returning to visit graves.

12. Elephants are one of the few species who can recognize themselves in the mirror.

Given what we now know about elephants, and what they continue to teach us about animal intelligence, it is more important than ever to make sure that these magnificent creatures do not vanish.

Check out some more fun elephant facts here and be sure to watch the TED-Ed Lesson Why elephants never forget - Alex Gendler

Animation by the ever-talented Avi Ofer

-

tenebrobscuro reblogged this · 5 years ago

tenebrobscuro reblogged this · 5 years ago -

tenebrobscuro liked this · 5 years ago

tenebrobscuro liked this · 5 years ago -

frederick03 liked this · 7 years ago

frederick03 liked this · 7 years ago -

kellarter reblogged this · 8 years ago

kellarter reblogged this · 8 years ago -

kellarter liked this · 8 years ago

kellarter liked this · 8 years ago -

cybersp4ce liked this · 8 years ago

cybersp4ce liked this · 8 years ago -

zielareczka liked this · 8 years ago

zielareczka liked this · 8 years ago -

unlikelylass liked this · 9 years ago

unlikelylass liked this · 9 years ago -

perfectcromulence reblogged this · 9 years ago

perfectcromulence reblogged this · 9 years ago -

msuprovenance liked this · 9 years ago

msuprovenance liked this · 9 years ago -

gatzbookbinding reblogged this · 9 years ago

gatzbookbinding reblogged this · 9 years ago -

dustyatticrarebooks liked this · 9 years ago

dustyatticrarebooks liked this · 9 years ago -

lynnemthomas liked this · 9 years ago

lynnemthomas liked this · 9 years ago -

lynnemthomas reblogged this · 9 years ago

lynnemthomas reblogged this · 9 years ago -

victoriansword liked this · 9 years ago

victoriansword liked this · 9 years ago -

maciekpawlikowski liked this · 9 years ago

maciekpawlikowski liked this · 9 years ago -

naoseiporquebruna-blog liked this · 9 years ago

naoseiporquebruna-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

tequilaxmockingbird reblogged this · 9 years ago

tequilaxmockingbird reblogged this · 9 years ago -

operationroom liked this · 9 years ago

operationroom liked this · 9 years ago -

skywithflame liked this · 9 years ago

skywithflame liked this · 9 years ago -

giantsteppes liked this · 9 years ago

giantsteppes liked this · 9 years ago -

everyone-needs-a-superhero reblogged this · 9 years ago

everyone-needs-a-superhero reblogged this · 9 years ago -

ligeia6 reblogged this · 9 years ago

ligeia6 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

awesomesiberiafan liked this · 9 years ago

awesomesiberiafan liked this · 9 years ago -

zorped reblogged this · 9 years ago

zorped reblogged this · 9 years ago -

zorped liked this · 9 years ago

zorped liked this · 9 years ago -

obsessedwithpretty79 reblogged this · 9 years ago

obsessedwithpretty79 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

obsessedwithpretty79 liked this · 9 years ago

obsessedwithpretty79 liked this · 9 years ago -

loki-does-what-he-wants liked this · 9 years ago

loki-does-what-he-wants liked this · 9 years ago -

catedevalois reblogged this · 9 years ago

catedevalois reblogged this · 9 years ago -

catedevalois reblogged this · 9 years ago

catedevalois reblogged this · 9 years ago -

catedevalois liked this · 9 years ago

catedevalois liked this · 9 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts