Lmao. Apparently, A Sufficient Number Of Puppies Can Explain Any Computer Science Concept. Here We Have

Lmao. Apparently, a sufficient number of puppies can explain any computer science concept. Here we have multithreading:

More Posts from Science-is-magical and Others

A human brain has around 86 billion neurons, and the communication between these neurons are constant. The sheer scale of these interactions mean a computer (an EEG) can register this electrical activity, with different frequencies indicating different mental states.

Sources

(Image caption: The above image compares the neural activation patterns between images from the participants’ brains when reading “O eleitor foi ao protesto” (observed) and the computational model’s prediction for “The voter went to the protest” (predicted))

Brain “Reads” Sentences the Same in English and Portuguese

An international research team led by Carnegie Mellon University has found that when the brain “reads” or decodes a sentence in English or Portuguese, its neural activation patterns are the same.

Published in NeuroImage, the study is the first to show that different languages have similar neural signatures for describing events and scenes. By using a machine-learning algorithm, the research team was able to understand the relationship between sentence meaning and brain activation patterns in English and then recognize sentence meaning based on activation patterns in Portuguese. The findings can be used to improve machine translation, brain decoding across languages and, potentially, second language instruction.

“This tells us that, for the most part, the language we happen to learn to speak does not change the organization of the brain,” said Marcel Just, the D.O. Hebb University Professor of Psychology and pioneer in using brain imaging and machine-learning techniques to identify how the brain deciphers thoughts and concepts.

“Semantic information is represented in the same place in the brain and the same pattern of intensities for everyone. Knowing this means that brain to brain or brain to computer interfaces can probably be the same for speakers of all languages,” Just said.

For the study, 15 native Portuguese speakers — eight were bilingual in Portuguese and English — read 60 sentences in Portuguese while in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner. A CMU-developed computational model was able to predict which sentences the participants were reading in Portuguese, based only on activation patterns.

The computational model uses a set of 42 concept-level semantic features and six markers of the concepts’ roles in the sentence, such as agent or action, to identify brain activation patterns in English.

With 67 percent accuracy, the model predicted which sentences were read in Portuguese. The resulting brain images showed that the activation patterns for the 60 sentences were in the same brain locations and at similar intensity levels for both English and Portuguese sentences.

Additionally, the results revealed the activation patterns could be grouped into four semantic categories, depending on the sentence’s focus: people, places, actions and feelings. The groupings were very similar across languages, reinforcing the organization of information in the brain is the same regardless of the language in which it is expressed.

“The cross-language prediction model captured the conceptual gist of the described event or state in the sentences, rather than depending on particular language idiosyncrasies. It demonstrated a meta-language prediction capability from neural signals across people, languages and bilingual status,” said Ying Yang, a postdoctoral associate in psychology at CMU and first author of the study.

Better late than never!

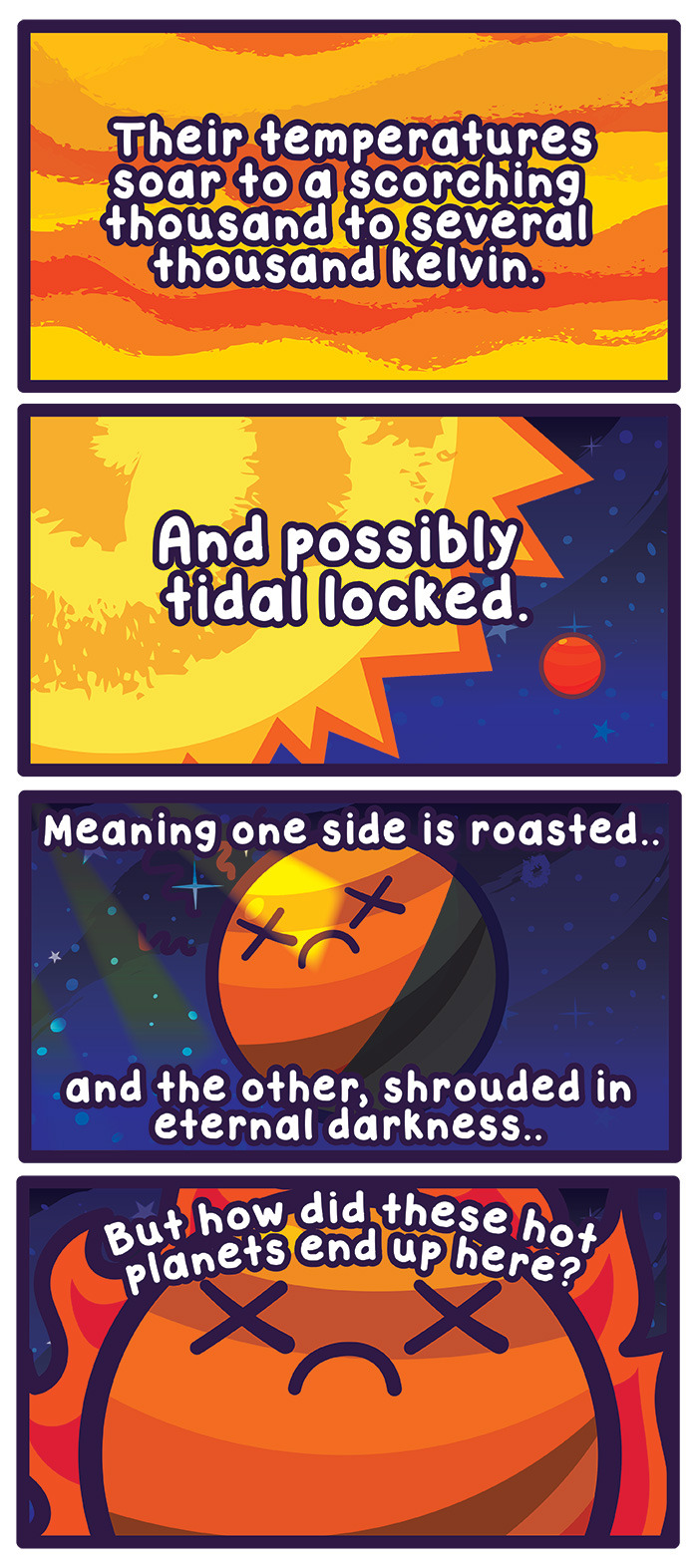

This week’s entry: Hot Jupiters

http://www.space.com/32011-extremely-hot-and-fast-planets-seem-to-defy-logic.html

https://astrobites.org/2015/03/04/hot-jupiters-are-very-bad-neighbors/

Trees ‘talk’ by exchanging chemicals. They communicate through underground fungi, and when they can recognize their relatives, they share nutrients. Basically, tree 'families’ help each other out. Source

the drum is filled with hot steam and then sprayed with cold water. the pressure on the outside of the drum is far more than inside. the pressures try to maintain and find balance taking the drum as a casualty.

Birds developed the unique vocal organ that enables them to sing more than 66 million years ago when dinosaurs walked the Earth, a new fossil discovery has shown.

But the earliest syrinx, an arrangement of vibrating cartilage rings at the base of the windpipe, was still a long way from producing the lilting notes of a song thrush or blackbird.

Scientists believe the extinct duck and goose relative that possessed the organ was only capable of making honking noises.

The bird, Vegavis iaai, lived during the Cretaceous era. Although its fossil bones were unearthed from Vega Island in Antarctica in 1992, it was not until three years ago that experts spotted the syrinx.

All birds living today are descended from a particular family of dinosaurs that developed feathers and the ability to fly.

The new discovery suggests the syrinx is another hallmark of birds that was absent from non-avian dinosaurs…

Y is for Ytterbium

Science Alphabet Game!

A is for Adenine!

Reblog with the next letter.

-

darkgreiga liked this · 3 years ago

darkgreiga liked this · 3 years ago -

codekarla reblogged this · 4 years ago

codekarla reblogged this · 4 years ago -

ink-spell-heart liked this · 4 years ago

ink-spell-heart liked this · 4 years ago -

science-and-syntax reblogged this · 4 years ago

science-and-syntax reblogged this · 4 years ago -

thezodiacco liked this · 4 years ago

thezodiacco liked this · 4 years ago -

noon-shadows reblogged this · 4 years ago

noon-shadows reblogged this · 4 years ago -

bdbooksrule liked this · 4 years ago

bdbooksrule liked this · 4 years ago -

culinaryspeyeder liked this · 4 years ago

culinaryspeyeder liked this · 4 years ago -

thekamiiiworld liked this · 5 years ago

thekamiiiworld liked this · 5 years ago -

oniiguro liked this · 5 years ago

oniiguro liked this · 5 years ago -

madness-on-fire liked this · 5 years ago

madness-on-fire liked this · 5 years ago -

batlegacy liked this · 5 years ago

batlegacy liked this · 5 years ago -

cezara liked this · 5 years ago

cezara liked this · 5 years ago -

bring-on-the-anime liked this · 5 years ago

bring-on-the-anime liked this · 5 years ago -

jayhawkgirlofeast liked this · 5 years ago

jayhawkgirlofeast liked this · 5 years ago -

kahfon liked this · 6 years ago

kahfon liked this · 6 years ago -

cxasandt liked this · 6 years ago

cxasandt liked this · 6 years ago -

iturbide liked this · 6 years ago

iturbide liked this · 6 years ago -

energywaste liked this · 6 years ago

energywaste liked this · 6 years ago -

sold-mars reblogged this · 6 years ago

sold-mars reblogged this · 6 years ago -

sold-mars liked this · 6 years ago

sold-mars liked this · 6 years ago -

your-fresh-laundry liked this · 6 years ago

your-fresh-laundry liked this · 6 years ago -

sierra117-renner reblogged this · 6 years ago

sierra117-renner reblogged this · 6 years ago -

boyuantai-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago

boyuantai-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago -

boyuantai-blog liked this · 6 years ago

boyuantai-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

khedixi reblogged this · 6 years ago

khedixi reblogged this · 6 years ago -

khedixi liked this · 6 years ago

khedixi liked this · 6 years ago -

pigeons-just-pigeons liked this · 6 years ago

pigeons-just-pigeons liked this · 6 years ago -

yuliamiloserdova liked this · 6 years ago

yuliamiloserdova liked this · 6 years ago -

anuctal liked this · 6 years ago

anuctal liked this · 6 years ago -

heybibleezra liked this · 6 years ago

heybibleezra liked this · 6 years ago -

ishtarterrauniverse-blog liked this · 6 years ago

ishtarterrauniverse-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

antithetical-dream reblogged this · 6 years ago

antithetical-dream reblogged this · 6 years ago -

antithetical-dream liked this · 6 years ago

antithetical-dream liked this · 6 years ago -

raccoonwithadream liked this · 6 years ago

raccoonwithadream liked this · 6 years ago -

littleemopandas reblogged this · 6 years ago

littleemopandas reblogged this · 6 years ago -

littleemopandas liked this · 6 years ago

littleemopandas liked this · 6 years ago -

skyykkeli reblogged this · 6 years ago

skyykkeli reblogged this · 6 years ago -

corettaroosa reblogged this · 6 years ago

corettaroosa reblogged this · 6 years ago -

corettaroosa liked this · 6 years ago

corettaroosa liked this · 6 years ago -

zorialdiamond-blog liked this · 6 years ago

zorialdiamond-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

walkingcursedimage liked this · 6 years ago

walkingcursedimage liked this · 6 years ago -

untrustworthyderp reblogged this · 6 years ago

untrustworthyderp reblogged this · 6 years ago