Ryoga

Ryoga

More Posts from Toivosworld and Others

Ever noticed how concerned she looks in this scene? She’s never seen that skunk look so beat up in his life. And that’s saying something since, you know, he’s been hit with everything under the sun. Just the expression on her face may indicate she cares a great deal for Pepe. Heck, her eyes are on him only and not on anyone else.

A white haired man in a long, pale robe who flees from us with his hands raised, 1794, William Blake

Medium: etching,ink,watercolor,paper

https://www.wikiart.org/en/william-blake/a-white-haired-man-in-a-long-pale-robe-who-flees-from-us-with-his-hands-raised-1794

Galaxies: Cities of Stars

Galaxies are like cities made of oodles of stars, gas, and dust bound together by gravity. These beautiful cosmic structures come in many shapes and sizes. Though there are a slew of galaxies in the universe, there are only a few we can see with the unaided eye or backyard telescope.

How many types are out there, how’d so many of them wind up with weird names, and how many stars live inside them? Hold tight while we explore these cosmic metropolises.

Galaxies come in lots of different shapes, sizes, and colors. But astronomers have noticed that there are mainly three types: spiral, elliptical, and irregular.

Spiral galaxies, like our very own Milky Way, look similar to pinwheels! These galaxies tend to have a bulging center heavily populated by stars, with elongated, sparser arms of dust and stars that wrap around it. Usually, there’s a huge black hole hiding at the center, like the Milky Way’s Sagittarius A* (pronounced A-star). Our galactic neighbor, Andromeda (also known as Messier 31 or M31), is also a spiral galaxy!

Elliptical galaxies tend to be smooth spheres of gas, dust, and stars. Like spiral galaxies, their centers are typically bulges surrounded by a halo of stars (but minus the epic spiral arms). The stars in these galaxies tend to be spread out neatly throughout the galaxies and are some of the oldest stars in the universe! Messier 87 (M87) is one example of an elliptical galaxy. The supermassive black hole at its center was recently imaged by the Event Horizon Telescope.

Irregular galaxies are, well … a bit strange. They have one-of-a-kind shapes, and many just look like messy blobs. Astronomers think that irregular galaxies’ uniqueness is a result of interactions with other galaxies, like collisions! Galaxies are so big, with so much distance between their stars, that even when they collide, their stars usually do not. Galaxy collisions have been important to the formation of our Milky Way and others. When two galaxies collide, clouds of gas, dust, and stars are violently thrown around, forming an entirely new, larger one! This could be the cause of some irregular galaxies seen today.

Now that we know the different types of galaxies, what about how many stars they contain? Galaxies can come in lots of different sizes, even among each type. Dwarf galaxies, the smallest version of spiral, elliptical, and irregular galaxies, are usually made up of 1,000 to billions of stars. Compared to our Milky Way’s 200 to 400 billion stars, the dwarf galaxy known as the Small Magellanic Cloud is tiny, with just a few hundred million stars! IC 1101, on the other hand, is one of the largest elliptical galaxies found so far, containing almost 100 trillion stars.

Ever wondered how galaxies get their names? Astronomers have a number of ways to name galaxies, like the constellations we see them in or what we think they resemble. Some even have multiple names!

A more formal way astronomers name galaxies is with two-part designations based on astronomical catalogs, published collections of astronomical objects observed by specific astronomers, observatories, or spacecraft. These give us cryptic names like M51 or Swift J0241.3-0816. Catalog names usually have two parts:

A letter, word, or short acronym that identifies a specific astronomical catalog.

A sequence of numbers and/or letters that uniquely identify the galaxy within that catalog.

For M51, the “M” comes from the Messier catalog, which Charles Messier started compiling in 1771, and the “51” is because it’s the 51st entry in that catalog. Swift J0241.3-0816 is a galaxy observed by the Swift satellite, and the numbers refer to its location in the sky, similar to latitude and longitude on Earth.

There’s your quick intro to galaxies, but there’s much more to learn about them. Keep up with NASA Universe on Facebook and Twitter where we post regularly about galaxies.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

History of Magick (pt. 1)

DISCLAIMER: Please keep in mind that this history series primarily focuses on the European aspects of magick. It is not an all-encompassing history. It should also be noted that I do not agree with the personal beliefs of many of the influential figures mentioned. This is a post on history, and the beliefs of individuals will reflect the context of their time. Be sure to research these figures before you make them into role models, and make your own informed judgement.

Magic, in some form or another, has been practiced since before written history. The public perception of magic has evolved over time, with practitioners prized, executed, adored, fantasised, and discriminated against. Regardless of its reception, magic has always been a fascinating topic, and it is only now that knowledge of magical practices is becoming widely available. The world ‘occult’ itself comes from the Latin occultus meaning ‘hidden’.

MAGIC VS. RELIGION

The separation of magic from religion is in its lack of involvement in a deity. A strict definition of magic could be an attempt to shape the various aspects of one’s life using methods that are not grounded in science, and typically do not appeal to a deity. A concept used to distinguish one from the other is ex opere operato (by virtue of the action). Essentially:

Magic: the practitioner expects the outcome to be as a result of the power of the ritual itself

Religion: the practitioner expects the outcome to be as a result of an intervening force

Nevertheless, the two often go hand in hand and are sometimes, especially in ancient history, indistinguishable from one another.

MAGIC AND WRITING

Just as most major religions are grounded in a holy text, magic has a close association with writing. The word ‘grimoire’ led to the modern word ‘grammar’, and the Egyptian god of magic, Thoth, was also the god of writing. This association is often found in societies where the majority of the population were illiterate and knowledge was hidden from the masses, thus making books a form of occult (or hidden) knowledge. Onwards of the 14th century the possession of magic books became a regular reason for prosecution - in 1319, the Franciscan friary Bérnard Delicieux was sent to prison for owning a book of necromancy, and a century later the Pope Benedict himself was accused of buying a similar book.

MAGIC VS. SCIENCE

In the Age of Enlightenment (17th-18th centuries), the occult branch of magic was replaced by rationalism, and the lighter branch of stage magic - sleights of hand and conjuring tricks aimed to delight. Magic was tamed and turned into a parlour amusement. Influential anthropologist James George Frazer speculated that ‘primitive’ magic would naturally develop into religion, and then science.

The ancient Mesopotamians and Egyptians believed that illness could be cured with spells - for them magic was already a science. Sir Isaac Newton was perplexed by the apparent ‘action at a distance’ caused by gravity, assuming it to be somehow magical. Much later, the sci-fi writer Arthur C. Clarke famously observed that ‘any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic’. For the English occultist Aleister Crowley, magic was ‘the science of understanding one’s self and one’s condition’, bringing us to the more contemporary understanding of the occult as being of benefit to the individual rather than solely impacting the physical world.

The end of the Enlightenment drew in a fascination with the desire to perform magic, with both Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung examining its origins. In 1944, Jung published Psychology and Alchemy, which drew parallels between alchemical symbols and psychological processes. In his Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis (1922), Freud claims that ‘words and magic were in the beginning one and the same thing, and even today words retain much of their power’.

While it is undecided whether magic is scientifically ineffable, a placebo effect caused by the brain or simply just another branch of science itself, the two topics are closely tied together throughout history. The idea can be succinctly summarised in this sentence: magic is simply unexplained science, and science is simply explained magic.

THE HERMETICA

Any history of magic, particularly Western magic, cannot be considered without discussion of the Hermetica, a powerful group of esoteric writings that can be traced back to Egypt (2nd-4th centuries AD). It consists of a series of dialogues mostly featuring Hermes Trismegistus (‘Hermes the Thrice-Great’). The dialogues deal with the nature of divinity, the order of the universe and even touch on subjects such as alchemy. Their central focus is the Corpus Hermeticum, a collection of texts translated into Latin from Greek by Marsilio Ficino at the end of the 15th century.

The Hermetic tradition feeds directly into Western esoteric traditions. French scholar of Western esotericism Antoine Faivre defines this tradition as operating by six key concepts:

Correspondences: the idea that there are sympathetic bonds within the universe, seen in the idea of macrocosm-microcosm (or the Hermetic saying ‘as above, so below’)

Living Nature: that all of nature is part of a conscious order, and that everything shares a life force

Imagination and Mediations: that rituals, symbolic images and intermediary spirits can connect different worlds and levels of reality

Experience of Transmutation: that esoteric practice can transform the individual, principally in the sense of a spiritual transformation

Practice of Concordance: that all religions, beliefs, etc. stem from a single, original principle, and that understanding this principle brings the various systems of belief into closer alignment

Transmission: that occult knowledge is transmitted from master to adept, often by means of an initiation process

This post is an excerpt from my personal grimoire. The main source is The Occult, Witchcraft & Magic: An Illustrated History by Christopher Dell.

So that could explain why Pepe is hitting on a random black bull with a white stripe???

GET YOUR SH!*T TOGETHER, PEPE!! It's not even a cat!

EN OTRO CUERPO | Miguel Gane

Te deseo lo mejor.

Ojalá encuentres en otro cuerpo

lo que yo no supe mostrarte.

Ojalá que las cosas te salgan bien,

y sobre todo ojalá que te quieran

como tú quieres,

es decir, desordenado e intenso,

ese amor de película francesa,

con su drama y su llanto,

pero con final feliz, al fin y al cabo.

Ojalá que tus planes se cumplan,

que tengas tus hijos como los sueñas,

y te mudes donde siempre has querido,

que llenes tu casa de libros y cine

y gente para no sentirte sola,

que vuelvas a París

y que no me recuerdes ni un instante.

Te deseo a alguien que llegue hasta tu altura,

tanto que se sorprenda cada día

de la montaña de mujer que eres.

Que busque en ti por el placer de buscar,

como aquel que sabe del tesoro

pero no quiere encontrarlo.

Que no quiera cambiar ni un centímetro de ti,

que ame tus errores

-pero no en silencio-,

y comprenda y respete tus heridas

sin pretender curarlas,

que acepte que siempre tendrás

la última palabra y que no te la quite

de la boca

porque justo ahí está tu fuerza.

Te deseo que no pierda nunca esa magia

que tiene el carácter

cuando las uñas se clavan en la piel.

Ojalá que te entienda, nena.

Tú siempre me dijiste que yo no sería capaz

y tenías razón.

Pero no te diste cuenta

de que precisamente por eso te quería.

Ojalá que des con quien siempre te tenga hambre,

que te lama tanto que encuentre nuevos sabores

en su lengua,

que disfrute tu piel, tus fantasías, tu sexo,

y sepa que por encima

de los cien cuerpos que tendrás discretamente,

también necesitas un alma

dispuesto a dejarse comer.

Te deseo, pues,

el amor de tu vida,

porque no se me ocurre mejor forma

de despedirme,

y que esta vez seas tú quien comprenda

hasta qué punto

llegué a quererte.

El alma está en profunda meditación durante todo el ciclo de la encarnación física.

Esta meditación es de naturaleza rítmica y cíclica, como lo es todo en el cosmos. El alma respira y por esto vive su forma.

Cuando la comunicación entre el alma y su instrumento es consciente y sostenida, el hombre se convierte en mago blanco.

Por lo tanto, quienes trabajan con magia blanca son invariablemente, y debido a la naturaleza misma de las cosas, seres humanos avanzados, pues se requieren muchos ciclos de vida para entrenar a un mago.

El alma domina su forma mediante el sutratma o hilo de vida, y a través de éste, vitaliza su triple instrumento (mental, emocional y físico) y así establece comunicación con el cerebro.

A través del cerebro, conscientemente controlado, el hombre es energetizado para realizar una actividad inteligente en el plano físico.

ALICE A. BAILEY

Inert are words that express indifference.

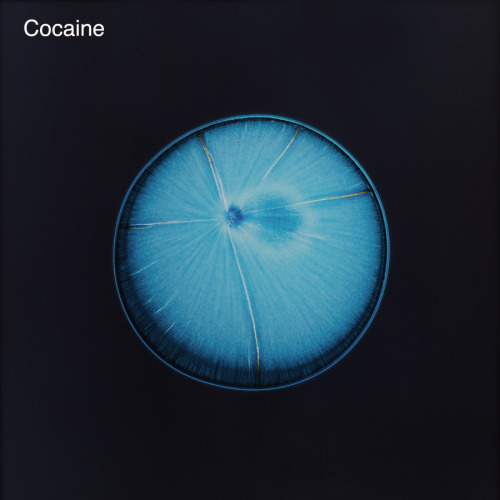

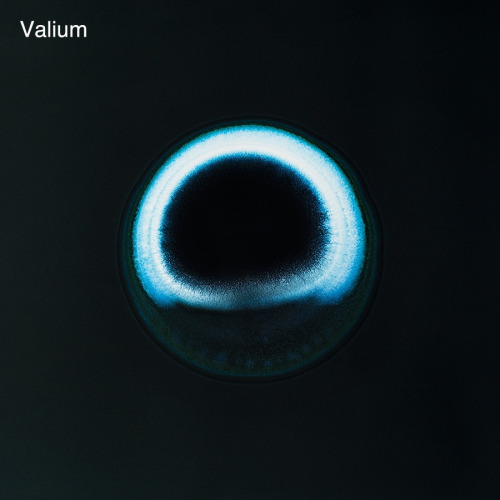

Photographer Sarah Schönfeld took liquid versions of drugs, both legal and illegal, and covered exposed negative film. Each drug interacted with the film differently, and the chemical reaction continued for variable amounts of time. She repeated the process for dozens of drugs and enlarged the negatives after the reactions were complete.

Visit her website to see more

“Ojos míos por qué están tristes a pesar de que me siento alegre palabras mías por qué son tan ásperas a pesar de que soy tierna actos míos por qué son tan estúpidos a pesar de que soy inteligente amigos míos por qué están agotados a pesar de que soy fuerte”

— Vera Pavlova