twilight-paradise88

"The ancient dome of heaven sheer was pricked with distant light; A star came shining white and clear, Alone above the night."

95 posts

Latest Posts by twilight-paradise88

Touka: *exists*

Kaneki:

TG:re Volume 5 Extra Translation

※

Like mortar in a mixer Three heads, melted thickly

Miracles have been used up long ago and lie cold on the concrete

Killed I killed Have I killed?

I was losing my grasp on reality, when the eyes of the heads opened wetly like genitals, to say hello

The heads whispered in Mother’s voice

“you” “you” “you”

“you” “how did you fool yourself into thinking you would be loved” “when you’re so ugly”

“uoh……..”

Gentle abuse, repeated over and over in “that box” The sky flickers, like traffic lights

Before I knew it, nine thorns sprang out from the chest cavity The diaphragm shivered, as if about to cry

(my body!)

I finally lost my grasp on reality, and I started climbing the steel tower The handrails I touched all turned black and rusted.

(I knew I was made of poison!) (No, it was that woman who was poison itself)

(climb, climb)

(not enough to die) (to a higher place, higher place, climb!)

※

The intestines of the dead, reaches out to the heavens from the tip of the steel tower.

The intestines were knotted together like rope. I desperately pulled the rope in.

squelch, squelch, squelch

The knot had grown long enough to reach the sun.

Tower of beloved corpses. With each pull I reach the peak, and the height increases. I cannot see the ground anymore.

The tower starts to shake widely, whispering in Mother’s voice.

“automatic failure at happiness, shapeless spawn”

(ahh)

“My dear lost one”

“Your parents failed in raising you”

And I died.

Image Source: Baidu

Major thanks to @makyun for helping me translate!

What's the theme of Choujin X?

So I've been wondering for a while, what idea does this story revolve around? What's the main conflict of the story? What concept should we pay attention to when reading this story? I can't claim to be 100% right or sure, but now that the story seems to have officially started, I'm going to try to articulate my ideas on this topic. By the way my ideas concerning the topic are heavily inspired by Jung.

Most fundamental to understanding the theme of this story is what exactly a choujin is. We've been given two main definitions, a person who becomes the form they desire, and a person who overcomes the limits of their humanity to use their ability. But why do such a minority of people have the capacity to become them?

The answer lies in the possession of a complex. A complex is a pattern of emotions, behaviours, thoughts and ideas which recur around a particular concept or theme. It's an unconscious way of seeing the world that influences how we act. But the issue is precisely that it's unconscious. The conscious self who wills events isn't aware of the complex that has formed within them, and that's usually the result of repressing a part of you that you don't like, so this complex tends to dominate and negatively affect the psychological well being of people.

Without such a complex one cannot become a choujin. When we combine what we know, we have a choujin as a person with a particular unconscious(at first) way of seeing the world and who tends to act accordingly with such a complex, and is fixated enough on such a theme and desire that they sacrifice their humanity for it. They are people who are governed by and hyperfixate on an idea so much that it is manifested through their capacities and harms their wholeness as a human being. In fact, I think that's what's expressed in the opening words of the story.

So there doesn't seem to be a moral status to being a choujin, but there's definitely something negative enough about it to warrant it being compared to a disease. And I think that's the status of it being a manifestation of a complex. A complex exists in the personal unconscious and exerts influence usually unwanted upon our actions. When one is brought into contact with what Jung calls the autonomous complex(the Shadow) it can possess us. When a complex possesses us we lose sight of who we are and unconscious impulses are brought to light. We lose control. The danger inherent in becoming a choujin is becoming consumed by our complex. When we are consumed by the shadow of this complex our humanity is shed for the continuous growth of the thing within us, and we become monsters. That's the affliction, the constant need to maintain control and humanity because of the tendency of the complex to take hold of us.(Note: Freud's name for the unconscious was the Id which is gotten from the German "It". There's something "other" about it and it fits quite well with the opening words in reference to becoming a choujin and it's relationship to complexes.)

Now I don't think Choujin are condemned or are essentially damned by their transformation, in a way, being a choujin can help one come in contact with their complex and start the journey Jung called individuation to integrate it. Through the dream at the heart of each person, the promptings of the ideal Jung referred to as the Self, people can be called back from despair to reconcile elements of themselves as we saw with Shiozaki. (Note: Chapter 1 of the series is called "Behold the Man" which could very well be a reference to Nietzsche's book of the same title with the subtitle: How one becomes what one is. This fits well with Jung's notion of the Circumbulation of the Self. We gradually become our true selves over time, as we strive to the ideal of the Self.)

So on a general level I believe the theme of the story will center around the integration of the shadow as it is manifested in our complexes. It's awakened, and it could be repressed or it could take over you, but the call of the story will be to overcome and integrate the shadow by finding your purpose in life.

“Never let the future disturb you. You will meet it, if you have to, with the same weapons of reason which today arm you against the present.”

— Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

This is all really cool and incredibly insightful. The coolest detail to me was probably Eren tying up his hair at the beginning as if he's trying to "keep it all together" at first, but the journey culminates in Eren's distressed and frustrated scream as his bun is undone. It gives a sense of him being overwhelmed and and a revelation of powerlessness.

Thoughts about the AoT Final season Op “The Rumbling”

Just wanted to ramble about some cool details found in the new opening “The Rumbling”. The opening begins by showing Eren, Mikasa and Armin. The trio is showcased in separate shots, reflecting on their separation during the recent events that have transpired in the story. As this first sequence draws to a close we see Eren taking a step, which then quickly transitions into a footstep of an Colossus Titan. I like this moment because the motion makes it seem like Eren is crushing that city. It is a cool and terrifying visual imagery but also foreshadows things that will happen in the future, since Eren will literally trample on the lives of others, as he activates the Rumbling.

Overall as the name of the song indicates, much of the song is focused on the Rumbling advancing on the main land.

Keep reading

Ohhhhh!!!

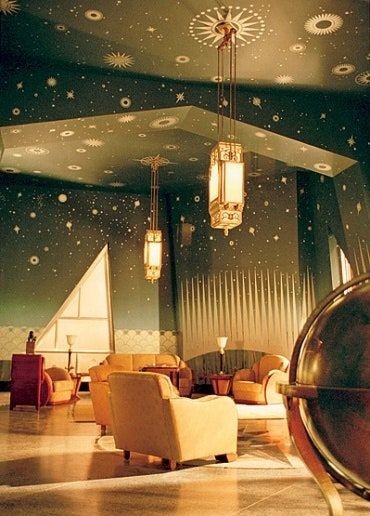

Source: https://www.marinabaysands.com/museum/exhibitions/attack-on-titan.html

Attack on Titan The Final Season Part 2 - Official Main Trailer

Part 2 of Attack on Titan: The Final Season will premiere on January 9, 2022.

“So long as man remains free he strives for nothing so incessantly and so painfully as to find someone to worship.”

— Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

[“One of the very hardest things about preventing and ending violence is that most of our work isn’t really about getting someone to stop being violent. Most of the time, that’s not the heart of the thing. The even-more-rigorous struggle is to cultivate all of the awareness and skills that would have been necessary for the violence not to have happened in the first place.

Which is why, when we talk about violence, we always end up talking about everything: slavery, binary gender, the original disconnection of humans from the rest of life on this planet, and so on. Solving violence is rarely as much about the moment at hand as it is about everything else that preceded it.

Which is where shame comes in.

As a therapist who has spent the last decade working with movement folks who are survivors of intimate violence—as well as with many people who have caused harm—I see shame as one of the most pervasive, painful, and insidious barriers to our efforts to fulfill the aspirations of transformative justice.

In order to develop real responses to the myriad harms in our lives—or even the capacity to develop real responses—we need to understand shame and develop tools for working with it, individually and collectively.

(…) Shame is different than guilt. While guilt focuses on our behavior (“I did something bad”), shame creates an identity: “I am bad.” Shame keeps us stuck, isolated, and hiding. With no way to escape from the totality of our belief (“I just am wrong”), we may do some of the following:

hide what we feel is bad about ourselves and try hard to pass as “good.”

overcompensate in other parts of life through overwork, caretaking, or perfectionism to make up for whatever is “wrong” about us.

defend ourselves from any insinuation that we might have done wrong, attempt to rationalize, or justify our actions.

blame someone else, try to divert responsibility, or shift the focus onto another.

attack anyone who draws attention toward the source of our shame, try to have power by dominating or shaming others.

numb through self-harming use of alcohol, substances, food, sex, technology, and so on.

Most of us use all of these strategies in different moments. Overaccountability and underaccountability are two sides of the same coin: “I can’t stand how bad I feel and can’t imagine making it right (overaccountability) so I’m going to hide that it (whatever it is) even happened, or lie about it or blame someone else (underaccountability).”]

Nathan Shara, Facing Shame: From Saying Sorry to Doing Sorry, from Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories From The Transformative Justice Movement

Nürnberger Land Franken Bavaria Germany by :

© P.Monatsberger

It still feels like a dream

Hey! I've been really enjoying a lot of your posts lately, and there's a question that's been bothering me that seems to be within your area of focus.

In SnK the theme of facing reality over escapism is very strong, and sometimes it seems like the story views things like dreams in a negative light, something that ought to be selflessly given up to truly change anything. Erwin's dream is said to be childlike, and Armin's dream(in chapter 90) is almost phrased in a way that makes it seem like it should be put away to deal with the real issue at stake.

But in other places the story seems to praise these dreams and ideals as things as noble as the freedom of humanity, Armin, Hange and Erwin all share very similar ideals, it's even called "The Survey Corps Way"

So my dilemma is basically about the main ideological thrust of the SC. Is the "unyielding desire for understanding" what lies at the root of the SC, or is it dedicating your heart to the common good of humanity? Should you give up on truth for the greater good, or are both of these ideals intertwined in some way? Is the desire for truth just another personal wish to be given up and passed on or is it instrumental to the essence of the Corps?

Hello!!!

Thank you so much for the ask and for reading the posts! I also have read some of yours a while ago, I find your perspectives also really interesting!!

Your points are pertinent, and though it might not be exactly an endgame answer I'll write, I think this will open a path to a deeper dive into the topic! (And sorry for the lateness!)

About Dreams:

What you said about dreams in snk is really true!

If we can try a broader perspective, though, I think we can also take that rather than trying to establish that personal dreams are negative or positive and you have to give up on them for the collective, SNK seems to be trying to show how dreams move people forward. What compromises them is what people are capable of doing to realize them. (And not always the wish of the collective is right...)

This is something that changes the perception a bit. For example, let's pick Erwin, Zackley, Armin, and Eren.

Erwin's personal dream wasn't bad or negative in nature, and the manga doesn't show it like that either.

I know sometimes this passage being referred to how people would react knowing Erwin's dream would be the most horrible thing that could happen to his reputation, but the thing is - it's not.

The proof is in chapter 85, where Nile (Commander of the Military Police) tells Erwin's full dream to Zackly (Commander in chief aka "Mr. President of Paradis"), and Pixis (Commander of the Garrison) and other military people. Rather than reacting horrified or disgusted at Erwin's dream, or regarding it as childish, they all show high respect to it. Zackley himself (who thought Erwin was like him) tells Pixis (who thought Erwin was like Zackley) and Nile that he should apologize to Erwin. Also, Nile has his face on the floor (ashamed). And to complete, Pixis calls Erwin a hero. So nope, the manga doesn't seem to be throwing much shade over Erwin's dream as a great deal seem to do...

I also particularly haven't seen anything bad in the nature of Erwin's dream. To prove how the world worked, how they lived under a manipulative government, how innocent people were killed for the sake of a lie that trapped people into a dangerous reality - how this is bad, negative, or to be seen as something full of depreciation? How can this be something horrible to the SC or humanity?

However, the problem that Erwin's dream had was that in order to achieve it, Erwin had to do a lot of gambles and took high risks that involved many people dying - and most of time without providing an "immediate meaning". And the lack of answers as well as the growing amount of sacrifices was beginning to make Erwin himself start to doubt himself as to what he was trying to accomplish for real (humanity’s freedom or his childhood dream), and later how far he was going to prove his dream.

When we get the context of their reality, if anything, if Erwin didn't have such drive to unveil the truth of the World (and saving the Survey Corps from being shut down forever), Levi would have died stuck in the Underground (or at the bottom of the well helpless), the Survey Corps would have shut in Keith's times, and Paradis would have perished with the Warriors invasions. But to Erwin - who realized he was not simply as devoted to Humanity’s freedom in a 100% selfless way as he thought he was - when he faced the people he had sworn to save reacting with such uncertainties, fear, and at a loss with the revelations and events of the Coup (Uprising Arc), there wasn’t guarantees that what he was doing was really going to result in anything ultimately salvific for everyone.

Erwin already felt responsible for all soldiers that were dying under his command while they were fighting to retake Wall Maria. But it certainly worsened after each new mission where people died to rescue Eren or take the other shifters. Eren had the key to solve what Erwin was looking for without barely any clear clue before, and Erwin wouldn't lose it. Then, with the coup, he began to wonder if it was really worth risking their world stability just to prove his father was right.

That's where Erwin stands when talking with Zackley in the carriage. Rather than wondering if how they lived was right or wrong at its roots, Erwin is worried about how everything can actually crumble once and for all. After all, the power of the Titans was a mystery to them, but he knew it was powerful and frightening - there were Shifters, there were Pure Titans, their primal defense against ultimate death was 03 huge Walls made of Colossal Titans, and there was the chance of the Titan power being capable of erasing and rewriting memories. So what would happen to everyone when Erwin finally made his dream come true? And that's when Zackley, much like Ksaver to Zeke, infects Erwin with a dangerous idea that was already sipping through the dam in his mind...

In chapter 62, Zackley insinuates to Erwin that he doesn't care about what he thinks he cares (humanity’s future), but rather that they're the same - satisfying their own dreams/wishes/will regardless of others. And Zackly says this because he had his dream of seeing the buffoons of the Monarchy being dethroned. He wanted to see them go down, what for the story and humanity was something good. But differently from Erwin, Zackley wanted to see them humiliated, put to ultimate shame. All because he never liked the pompous bastards...

So, while it was thanks to wanting to realize his life dream that Zackley helped Erwin to make the coup happen, Zackley wanted more. And this is where the talk about Pixis and Zackley about people being disgusted over the military is 100% for real - Zackley's dream to see those monarch men utterly humiliated gave birth to a monstrosity. He created the horrifying shit-feeding machine, put into action, and wanted to open an exposition so people could see it too. This is so sickly twisted that Zackley terrifies and disgust me in ways I can't describe. And, for thinking Erwin was somehow more preoccupied with saving himself than survivors/humanity, and more aligned with Zackley's selfish mentality, Pixis reprimanded Erwin in chapter 63.

That's why they talk about apologizing to Erwin in chapter 85. They're wrong about him. Yet, they all had already planted and watered the seeds of doubt and shame in Erwin...

Thanks to Levi, though, Erwin got over it. And, as Yams said that when facing death people reveal their true nature, Erwin proved his battle was for humanity. It was never to simply satisfy himself. And when needed, when his dream diverged from the responsibility needed to save humanity, Erwin chose to do what was right. (And that's why this man is on my top fav characters!

Now, Armin's dream.

His dream is one of the nicest and most pure dreams in the story. It's a dream born out of curiosity, of simply humanity, free of traumas and looking hopefully at the future. And imo, it's not a childish dream either because it was rooted in significant information provided by a forbidden book, with descriptive images giving more solid clues that those things could actually be true. So, again, contrary to the "over idealistic" idea people believe Armin had, his dream is actually based on scientific evidence. All they needed was to be seen to be proved true (or false) - which demanded not be bound to the simple reality they lived in. And, as Armin said in chapter 72, they should start with seeing the ocean, and the things that lived there.

His dream is in fact so moving and hopeful that even Levi - who lived afraid of forming close relationships for fear of losing people and hesitates in harboring much hope for the better - is shown soft and touched by the enthusiasm in Armin like we have never seen Levi look in the manga.

This moment was so precious for Levi as much as it was for Armin, imo. More so because it's one of the reasons Levi stares at the eyes of the present-future and sees the beauty of freedom there. A type of freedom close to what he sees in Kenny when he gave up his dream, and then when Erwin gave up his doubts over what to do, over what kind of man he was, and accepted he was doing the right thing even if it was costing his life and dream.

Armin wasn't a slave to his dream - the dream had set him free...

And Armin's dream is a beautiful inquisitive mind preparing to become a pathfinder - and his heart is unchained and at ease, contrary to the other two. So I fail again to see the negativity in this type of dream itself for someone having to give up for the greater good. Which brings us again to the problem being what people would be capable of doing to realize their dreams.

Involuntary, Armin had to shoulder the responsibility of eating a once friend, becoming a Titan, and being chosen to be saved over the life of Humanity’s Hero, Commander Erwin Smith. He never asked for this, but now he had to carry it. Armin - the kid who had extreme self-loathe and insecurity - knew he could never replace Erwin, but now he will have to do the impossible to pay back the responsibility placed upon him. Still, Armin didn't give in to despair - but adapted to it, slowly and as best he could. Or at least tried it...

Later, just as he said, Armin began fulfilling his dream with Eren (and his friends) when they reached the ocean. He knows he is going to die in 13 years. He knows Titans are made by people on the other side of the ocean. He knows the 2nd round of their battle is just starting. Yet, Armin is still advancing with hope.

When they crossed the ocean for the first time, though the world wasn't exactly as Armin expected, he still wasn't dejected or disillusioned (like Eren). He, like Erwin, held back the full completion of his dream momentarily so as to do what was right and more urgent at the moment. He took the responsibility of the present so as to try ensuring there would actually be a future.

But reality struck him mercilessly. To survive, to have a chance with his friends and his people's future, Armin was forced to do terrible things. He crossed the beautiful blue ocean of the start of his dream to turn it into a dark sea of scarlet blood on the opposite shore, in Marley; he killed countless of innocent people for the greater good; he killed some friends and compatriots who were so scared of being exterminated and die that they miserably sided with the despicable idea that genocide was going to save them.

Then, the final trial came for him: Armin had to kill his best friend, his family, because Eren was deliberately mass-murdering and destroying the planet. He had to give up on the brother he got gifted from life, who always came to his rescue whenever he was in trouble no matter what - from boys doing bullying, to the mouth of a Titan eating him, to cannonballs, to Trost’s gate rupture, to hordes of Titan about to kill him again, to Reiss Titan, to Levi wanting to save Erwin over him… Armin had to give up the hope of saving half of him.

The thing Armin dreamed the most was to one day see the outside world starting by all the wonders in the book (and fulfill the promise with Eren they would do it together too), and reality forced him to choose between watching 99% of the world die under a (false) premise of security for his motherland and the responsibility of saving the world by killing his chosen brother because Eren wouldn't stop and listen. Reality in snk was a fucking bit*ch, and I hate it so much…

Now Eren… is complicated.

Imo, he is the one who gets closer to having a dream truly negative in at least 90% by its nature because he couldn't see the right time to get a hold of himself and give up, costing 80% of humanity. But it apparently seems that if he hadn't done what he did, Ymir would be a slave forever in Path because seeing Mikasa kill her monstrous lover was what made her free. Eren was the most difficult contradiction (and I still don't have my thoughts over this whole triangle of them…).

However, we know he wanted with his dying breath to wipe out "every last one of those animals of the face of the Earth", aka the Titans. However, Eren seems to have been dreaming of being the one accomplishing whatever he himself ever wanted rather than just exterminate the Titans.

Like, Eren didn't dream of seeing the wonders Armin showed him in his forbidden book - it seems more like he just wanted to feel the sensation of being the one doing it, as if being capable of doing it proved he was living "without borders". Since Carla's death, he wanted to stop feeling powerless and weak, and for this he embraced the power of the creature he hated the most as his power without batting an eye. Yet, even having a power rare people had, Eren failed so many times, and hundreds of people died just to save him. He was over and over reminded of his weakness, and he loathed that. In the Uprising Arc, when he realized he wasn't "special", and the responsibility of his and his father's actions were dawning on him, Eren wanted to die.

Then, when he discovered that the world wasn't the way he wanted, Eren looked even more compelled to move forward with his destructive plan. And when he got the God-like powers who gave him the power to finally be capable of doing anything he wanted, Eren proved that he was indeed the last person on Earth that should be entitled with such power. Imo, chapter 131 is one of the most stunning for his character, and I can't explain how unnerving and incredible I think it's how Eren could show such expressions of delight while a massacre was going right under his foot. I can’t wait to see it animated…

So, that's my take about personal dreams in snk: they're not inherently negative most of the time. However, there are times that the dreamer is forced to face harsh events of reality to achieve it - or they just get the luck to be graced with an opportunity to fulfill it -, and what they do in those circumstances is what consolidates their nature.

Not giving up on them, but adjusting them to reality through thick and thin is a quality that shows perseverance and can be very fortunate to change reality to a better outcome. But other times, it's best to give up. Erwin died with the military knowing his personal dream and also because of it calling him a hero, while Eren died known for most people as a mass murderer and a devil for the world, a savior-transgressor friend for his friends that were free from the Titans, and as a martyr for Yeagerists. Such is the complexity of living in the human world and our variable nature.

As for the "greater good" or freedom of humanity dream, Yams also threw some shade over these ideas too. Like, in chapter 128 is one of them - when Yelena shows how bloody, violent, and at the cost of innocent enemy lives a "save the world" idea can lead to. Sometimes people can fall short in a sea of corpses and deluded driving by this idea when it's overly romanticized, idealistic. Sometimes to free humanity looks heroic, but in fact to reach it, the path is paved in a lot of non heroic actions. "Life sacrifices" are said to be needed - but if each person is special in it's own because they're born into this world, then what gives us the right to judge whose lives have to be sacrificed?

We have to watch out for our purposes constantly, and be grounded to the facts of reality when dealing with people's lives.

About the Survey Corps

Is the "unyielding desire for understanding" what lies at the root of the SC, or is it dedicating your heart to the common good of humanity? Should you give up on truth for the greater good, or are both of these ideals intertwined in some way? Is the desire for truth just another personal wish to be given up and passed on or is it instrumental to the essence of the Corps?

In advance, I would say they're somewhat intertwined, but maybe the desire for change is what lies at the root of the Survey Corps together with dedicating the heart for the greater good.

Because the "unyielding desire for understanding" is the best quality for a Survey Corps Commander, rather than all the members of the SC members. As we know, not everyone feels moved by the deep desire to know more about the world as the main reason why they support, join and stay in the Survey Corps. Some joined for the dissatisfaction of their current way of living, some wanted to make a name, some wanted to destroy every Titan, some just wanted to protect their families, and so on...

Something that is also interesting is that Hanji says in her close up interview that the Survey Corps isn't Killer Corps, but Survey. They're not made to exterminate the Titans, but their main goal is to understand the truth of the World and explore what is unknown to give humanity freedom. Freedom that was primarily to “seek for” ways to expand the scope of human activities.

However, to accomplish whatever they wanted to change, they had to be ready to dedicate themselves to the cause. And in the face of death, they would entrust their surviving comrades to make their sacrifices and hopes one day pay off.

So in the end, it's the balance of all things considered that could in fact provide the necessary forces to move the Survey Corps (and humanity) forward.

Royal Blood; Historia Reiss ¶ ヒストリア・レイス

T w i t t e r: sucubuss_art

“ If other people are going to steal my freedom... i’m going to steal theirs “

T w i t t e r: sucubuss_art

SNK 137: To see the world in a grain of sand

A story that traverses 2000 years of history, across the vast expanse of time and space, war and empire, great despair and fragmented hope, legends of gods and devils.

SNK features immense scales that can evoke sheer awe, from its temporal and thematic scope to its pure visual spectacle, all the way to the world’s destruction.

And yet in the midst of the breathtaking, terrifying magnitude of the end of the world, it has culminated here, in the memory contained within a single leaf minuscule as a grain of sand against the death marching across seas and continents.

A leaf that contains a childhood memory utterly insignificant, utterly meaningless in the futile battle against geopolitical conflict, human nature, the curse of Ymir that becomes fate itself.

Yet it is also a memory that means everything.

The fate of the entire world, contained within a single leaf half-buried in the eternal sands transcending time and death.

“The reason I was born…” was not to save the world, or to be a hero; the reason was to simply exist in these moments when one can feels distinctly, ‘I’m here, and I’m glad to be alive.’ Approaching the end of this two thousand year story, Armin’s quiet affirmation captures fundamentally what freedom is, and what it is to want to live in the world.

Arguably without exception, everyone experiences at least once in their life such moments. Even when in the depths of despair, depression, or apathy, still suddenly, if only for one fleeting instant, we feel intensely that maybe it’s okay to be alive when experiencing such trivial things as the sunlight through the trees, a glimpse of the achingly blue sky, or the certainty that we have made a connection with someone through a word, a touch, or a smile. These distinct moments are interspersed as small, flickering lights strung together through the darkness of life’s struggles.

This is Armin’s answer to Zeke’s questions: “You know that to live… means to one day die, does it not?” Where is the freedom in the endless struggle to avoid the punishment of fear and suffering we confront when life’s empty, frantic quest to multiply is threatened? What is the purpose of perpetuating one’s days of suffering without ever knowing if it means anything at all?

Armin’s answer is not convincing or changing Zeke’s mind as such, rather he is merely reminding Zeke of what he has already experienced, of what he already knows, unconsciously: that somehow, there is meaning in feeling the wind against your skin, in the repetition of throwing and catching a baseball back and forth with someone you call family.

Or to be more precise, perhaps there is no logical meaning in these moments at all, but that doesn’t stop these moments from being meaningful.

“in our bewilderment we see no rule by which to guide our steps day by day; and yet every day we must step somewhere.”

It’s not a perfect answer; perhaps it’s not an answer at all. Yet it is enough to convince us to take another step forward, because unlike logical reasoning or Zeke’s scientific rationalizations, the feeling of life in such trivial moments carries an irrefutable personal certainty of gratitude for being alive.

SNK generally prioritizes the grand over the trivial or strictly ‘relatable’, but we get here something so purely and immediately human, grounded in an intimate, even mundane way that is interwoven with the cosmic realm in which they are having this conversation.

It feels indeed that put upon a simple leaf, of a baseball, is a uniquely cosmic weight, as the weight of everything, all this history and eternity, is resting on this quiet reflection.

To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand And Eternity in an hour

- William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence”

SNK 139.5: Towards the Final Pages with no Final Answers

The final pages of the updated ending are bold, but I think ultimately more evocative than the original preliminary ending.

Even after the intensely polarized reader reception that took issue with the lack of storytelling precision and clarity when it was most needed, SNK chose to end with a decisively ambiguous symbol. In literature, a symbol is something that clearly means something -- but with the most "literary" symbols, their meaning cannot be absolutely defined; any attempted answer as to what a symbol represents has no finality or certainty, and interpretation will remain ever open to debate. A symbol both invites and resists interpretation.

Naturally, the immediate response to the symbolic tree on the final page is to try answering the invitation to the question, "What does it mean?"

One prominent answer I've seen is that it symbolizes the continuation of the cycle of war and violence either because a) of the symbolic parallel to Ymir or b) on a more literal level, that it implies the actual potential revival of new era of Titans. A reasonable interpretation either way, but also, I think, an incomplete one.

The first reason for this is that "the endless cycle of war" was already clearly and powerful represented in the preceding panels:

The cycle of war was already continuing in the decades or centuries before the child arrived at the tree. A culminating image symbolizing the persistence or resurgence of an era of war as the final panel would thus arguably be redundant and unnecessary.

Furthermore, the chapter is entitled "Toward the Tree on That Hill." If the tree were simply a symbol of war, by implication the chapter could equally be called 'toward the endless cycle of war'. But such a relentlessly bleak and tonally flat ending sentiment would be firmly incongruous with the story's recurrent conviction in the equal cruelty and beauty of the world -- a conviction that I believe it has been faithful to all the way to its end.

The Long Defeat

But while on this topic of war, let's linger a moment on the "cruelty" side and the consequence of this wordless construction and subsequent destruction of a city -- the most bold and possibly controversial additional panels that are also my personal favourite additions.

One objection that has emerged against this brief sequence of Paradis' apparent destruction is that it renders the entire story to be "pointless". Eren's 80% Rumbling, Armin's diplomatic peace talks between the remnants of the Allied Nations and Paradis, and before that, the proposal of the 50-year plan and Zeke's euthanasia plan... everything, to the very beginning to the Survey Corps' dreams of some kind of freedom; was it all for nothing? All that striving, that hope, that final promise bestowed upon Armin: was it all a pointless story? Even more radically, is the story suggesting that Eren might as well have continued the Rumbling to 100% of the earth? Was Zeke's euthanasia plan the cruel but correct choice all along? What was the point of rejecting the 50-year plan if that had a greater chance of success at preventing this outcome?

I think Isayama suddenly pulling back to such a long-term view of history to the scale of decades or even centuries into the future calls for a reorientation in attitude towards exactly what kind of story we have been reading. Yes, if the metric is Paradis' survival, maybe it was indeed all "pointless". But that's also to say that, on the broadest scale, SNK is a story about futility, that it is a deliberate representation of the struggle to make one's actions historically meaningful.

In the long view of history, all the events, from Grisha running beyond the wall to see the airships and the first breaking of Wall Maria to Erwin's sacrifices, Paradis' discovery of the outside world, and finally to the Battle of Heaven and Earth, it would all merely be a handful of chapters in the history textbooks of the future. A future in which war and geopolitical conflict will continue even without Titans. That does not mean that all paths to the future are equal -- the 50-year plan would not have put an end to Titans, and Zeke's euthanasia plan distorts utilitarian ethics into just another form of oppression; there are better and worse decisions that lead to more and less degrees of suffering, but no decision can ever be the final one.

The additional panels remind us that in history, there never exists a singular "Final Solution". The reason there are readers who vehemently support Eren to have flattened 100% of the world, and the reason the Paradisians supported the oppressive, authoritarian, proto-fascist Jaegar Faction under Floch and even after the Rumbling, is that because they want to believe that a Final Solution to end conflict exists and will work. They resist the fundamental uncertainty and complexity of the situation, instead preferring a singular, unified, and coherent Answer to Paradis' struggle to survive. I'm reminded of the scholar Erich Auerbach's theorization of why fascism appealed to many people during periods of political and social crisis, change, and uncertainty. Writing in exile after fleeing Nazi Germany, he observed that:

"The temptation to entrust oneself to a sect which solved all problems with a single formula, whose power of suggestion imposed solidarity, and which ostracized everything which would not fit in and submit - this temptation was so great that, with many people, fascism hardly had to employ force when the time came for it to spread through the countries of old European culture." (from Mimesis p. 550)

This acutely describes the Jaegar Faction's rise to power and continued dominance in Paradis. But their promise of unity, of a single formula to wipe out the rest of the world either literally through the Rumbling, or to dominate them with military force, is a false one. Even if Eren had Rumbled 100% of the world instead of 80%, history would still go on. The external threat of the world may have been eliminated, but internal conflict and violence would still continue onward throughout the generations born on top of the blood of the rest of the world. Needless to say, out of all the options, Eren's 80% Rumbling is the very epitome of perpetuating the cycle of violence as it creates tens of thousands of war orphans like Eren once was, and it would justify employing violence for one's own self-interest to an extreme degree. For the generations to come that would valourize Eren as a hero, it would set a dangerous precedent for what degree of destruction is acceptable for self-defence -- nothing short of the attempt to flatten the entire world. It is no surprise that Paradis would meet a violent end when its founding one-party rule of the Jaegar Faction has their roots in such unapologetically bloody foundations.

Neither the 80% Rumbling nor the militaristic, ultra-nationalistic Jaegar faction that come to govern Paradis are glamourized as the "correct" solution to ensuring Paradis' future. (This can also put to rest any accusations of SNK's ending as "fascist" or "imperialist" propaganda, since the island's modern nation that they founded ends in war. All nations must fall eventually, but not all do in such blatant destruction). Importantly, neither is Armin's diplomatic mission naively idealized as that which permanently achieves world peace. No singular or unifying formula can work because reality is complicated. Entrusting oneself to seemingly simple Answers is simply insufficient, even if they are ideals of peaceful negotiation; that method may work given the right conditions, but the world will always eventually complicate its feasibility.

After all in the real world, there's the absurd irony that some in the West had called the First World War "The War to End all Wars". These days, WWI is merely one long chapter in our textbooks just a few pages away from the even longer chapter of the Second World War that is followed by all the rest of the conflicts that have followed since then even with the establishment of diplomatic organizations like the United Nations. In this sense, showing Paradis' eventual downfall is perhaps the only way to end such a series that is so concerned with history, from King Fritz's tribal expansion into empire, the rise and fall of Marleyan ascendency, and finally of the survival and apparent shattering of Paradis.

From its beginning to its end, SNK has poignantly evoked J.R.R. Tolkien's conception of history as The Long Defeat. In one character's words, "together through ages of the world we have fought the long defeat". That is to say, "no victory is complete, that evil rises again, and that even victory brings loss".

No heroes, only humans

Eren's desperate, fatalistic resignation to committing the Rumbling, along with the characters' rejection of all the rest of the earlier plans to ensure Paradis a future, are merely the actions of human beings to that began with the need to find not even necessarily a Final Answer, but at least an acceptable and feasible one for the time being. But the characterization of Eren's confusion, childishness, and regret in the final chapter is startlingly real in how it demonstrates how, all along, we have been dealing not with grand heroes, but simply people who have no answers at all. SNK has always been about failures - and often ironic failures; it has always been a story about painful and frequently futile struggle.

People make mistakes, they can be short-sighted, selfish, biased, immature, petty, and irrational, and I think the ending follows through with depicting the consequences of that.

Erwin's self-sacrifice before being able to reach the basement (and his regression to a childhood state in the moments before his death), Kenny's futile chasing after that universal compassion he had seen in Uri, Shadis never being acknowledged by history despite his final heroic action, and so on -- these stories of ironic, futile failures are still meaningful in their mere striving. Eren's ending and Paradis' demise despite Armin's endeavour to ensure them a peaceful future are entirely consistent with this.

SNK certainly follows the shounen trope in which young individuals are bestowed great power and correspondingly great responsibility, and must then reconcile the burden of possessing that greatness on which the fate of the world depends. Yet it is equally defined by its representation of the state that us normal human beings confront everyday: the struggle against the apparent powerlessness to enact any meaningful or lasting change at all. Simultaneously, this helpless state does not exempt us from the responsibility to act in whatever small capacity we are able to resist oppression, ideological extremism, and the perpetuation of violence.

Towards That Symbol

That was a rather long but vital digression about the additional "construction and destruction" pages. To return to the issue of the symbolism in the final panel, here I will turn from seemingly affirming the tree as symbolizing the cycle of violence, towards what I think is the greater complexity of what the tree might "actually" symbolize.

As I've said above, I don't believe that the final chapter title is synonymous with 'toward the endless cycle of war'. In tone, theme, and characterization, SNK has always been defined by the tension between cruelty and beauty, the will to violence and the underlying desire for peace, and the rest of the contradictory impulses that all simultaneously coexist. The end of SNK as a whole commits to a similar lack of closure, ambiguity, and interpretive openness.

So far I have rambled on about only a view of the perpetual "cruelty" of history. Where, then, is the "beauty"?

In short, the "tree = cycle of violence" interpretation is obviously based on how that this tree recalls the original tree in which the spine creature, as the source of the power of the Titans, resided. But it's worth first considering, what exactly is this creature? We seem to get our answer in the chapter that most precisely crystallizes the dual "cruelty and beauty" of the world:

The spine creature might be said to be life itself. Or more specifically, the will of life to perpetuate itself, for no reason at all but for the fleeting moments in which we feel distinctly glad to have existed in the world.

The creature at the source of the Titans, and in extension the Titans themselves, is neither inherently a positive or negative, "good" or "evil", creative or destructive force. It's both and all of those at once. As with any power, the Titans were merely a tool that was put to use to oppressive ends.

So as I now suggest that the tree at the end is symbolically a "Tree of Life", I don't at all mean "life" in the typically celebratory or optimistic sense: rather, I mean it in the ambiguous, ambivalent, uncertain, and complex sense that has been evoked throughout the above discussion of the inevitable continuation of war.

The title "Toward The Tree on That Hill" is derived from its associations with Eren and Mikasa, but more specifically of course, from Armin's affirmation of existence. However, the tree as a symbol of existential affirmation is undercut with the revelation that, despite Armin's diplomatic mediation between the Allied Nations and Paradis, the island nation never escapes war just as no nation in the history of the earth has ever fully escaped war.

The image of Armin running toward that life-affirming tree by the end becomes twisted and complicated, as the image of the anonymous child approaching the Tree of Life evokes both awe at its beauty and grandeur, and a deep dread at the foreboding of its cyclical return to Ymir's tree that signalled the beginning of a bloody era.

And I think that is precisely it: Life is not some idealized, beautiful vision that we always want to run toward; it is also ironic, complicated, and dreadful. It is ambivalent. Like a literary symbol, the meaning of life cannot be pinned down absolutely. The tree therefore becomes itself a symbol of uncertainty, of an open future that is cyclical both in its beauty and war.

As a final observation, it is surely no coincidence that, the small, black, birdlike silhouettes of the war planes destroying the city from the sky is replaced by the similarly small black silhouettes of birds in the final panel.

If the birds represent freedom from war, the irony is that the immediately surrounding land appears to be one completely empty of people save for the exploring child; it is a freedom attained only without people's presence. Yet at the same time, a child from some existing civilization has reached it; perhaps it is freedom that they have reached, perhaps it is something else that they see in the tree. What is it that they were looking for? What does the tree and its history represent for the child, and what does it mean for their future? Alternatively, does the child-in-the-forest imagery negatively recall the warning that the world is one huge forest of predator and prey that we need to protect children from entering?

Rather than providing answers, this tree embodies all of the potential questions, and all of the potential answers. These possibilities will unfold themselves into an uncertain future beyond the chapters of history that Eren, Armin, Mikasa, Zeke, Erwin, and all the rest of the characters were part of and left their mark on; and whatever future this child will witness or create, it will similarly be one of the struggle against futility, as the journey begins anew with each generation in every new era. Neither - or both - hopeful or despairing, the final image of this tree, just like life itself, contains those innumerable irresolvable tensions as it gestures towards all possibilities, both oppressive and free.

The Heights by Quentin Stipp

進撃の巨人 The Final Season Pt. 2 Preview

9th January 2022