From The Memory Palace, By Nate DiMeo

from The Memory Palace, by Nate DiMeo

More Posts from Jjgaut and Others

*curtsies* So, I really, REALLY don't want to offend anyone, Duke, but a question has been bothering me for a really long time and I was afraid to ask it because I didn't want to piss off anyone and since you're really eloquent and knowledgeable, I thought I'd ask you. So here it goes: you always say that arts and sciences are equally important, but how can analysing Chaucer or ecopoetics or anything similar compare to biomedicine or engineering in improving human lives? I'm genuinely curious!

*Curtsies* All right. Let me tell you a story:

When I lived in London, I shared a flat with a guy who was 26 years old, getting his PhD in theoretical physics. Let’s call him Ron. Ron could not for the life of him figure out why I was wasting my time with an MA in Shakespeare studies or why my chosen method of providing for myself was writing fiction. Furthermore, it was utterly beyond him why I should take offense to someone whose field literally has the word “theoretical” in the title ridiculing the practical inefficacy of art. My pointing out that he spent his free time listening to music, watching television, and sketching famous sculptures in his notebook somehow didn’t convince him that art is a necessary part of a healthy human existence.

Three other things that happened with Ron:

I came home late one night and he asked where I’d been. When I told him I’d been at a friend’s flat for a Hanukkah celebration, he said, “What’s Hanukkah?” I thought he was joking. He was not.

A few weeks later, I came downstairs holding a book. He asked what I was reading and when I said, “John Keats,” he (and the three other science grad students in the room) did not know who that was. This would be like me not knowing who Thomas Edison is.

One night we got into an argument about the issue of gay marriage, and at one point he actually said, “It doesn’t affect me so I don’t see why I should care about it.”

Now: If Ron had ever read Number the Stars, or heard Ode to a Nightingale, or been to a performance of The Laramie Project, do you think he ever would have asked any of these questions?

Obviously this is an extreme example. This guy was amazingly ignorant, but he was also the walking embodiment of the questions you’re asking. What does art matter compared with something like science, that saves people’s lives? Here’s the thing: There’s a flaw in the question, because art saves lives, too. Maybe not in the same “Eureka, we’ve cured cancer!” kind of way, but that doesn’t make it any less important. Sometimes the impact of art is relatively small, even invisible to the naked eye. For example: as a young teenager I was (no exaggeration) suicidally unhappy. Learning to write is what kept me (literally and figuratively) off the ledge. But I was one nameless teenager; in the greater scheme of things, who cares? Fair enough. Let’s talk big picture. Let’s talk about George Orwell. George Orwell wrote books, the two most famous of which are Animal Farm and 1984. You probably read at least one of those in high school. Why do these books matter? Because they’re cautionary tales about limiting the power of oppressive governments, and their influence is so pervasive that the term “Big Brother,” which refers to the omniscient government agency which watches its citizens’ every move in 1984, has become common parlance to refer to any abuse of power and invasion of privacy by a governmental body. Another interesting fact, and the reason I chose this example: sales of 1984 fucking skyrocketed in 2017, Donald Trump’s first year in office. Why? Well, people are terrified. People are re-reading that cautionary tale, looking for the warning signs.

Art, as Shakespeare taught us, “holds a mirror up to nature.” Art is a form of self-examination. Art forces us to confront our own mortality. (Consider Hamlet. Consider Dylan Thomas.) Art forces us to confront inequality. (Consider Oliver Twist. Consider Audre Lorde. Consider A Raisin in the Sun. Consider Greta Gerwig getting snubbed at the Golden Globes.) Art forces us to confront our own power structures. (Consider Fahrenheit 451. Consider “We Shall Overcome.” Consider All the President’s Men. Consider “Cat Person.”) Art reminds us of our own history, and keeps us from repeating the same tragic mistakes. (Consider The Things They Carried. Consider Schindler’s List. Consider Hamilton.) Art forces us to make sense of ourselves. (Consider Fun House. Consider Growing Up Absurd.) Art forces us to stop and ask not just whether we can do something but whether we should. (Consider Brave New World. Consider Cat’s Cradle.) You’re curious about ecopoetics? The whole point is to call attention to human impact on the environment. Some of our scientific advances are poisoning our planet, and the ecopoetics of people like the Beats and the popular musicians of the 20th century led to greater environmental awareness and the first Earth Day in 1970 . Art inspires change–political, social, environmental, you name it. Moreover, art encourages empathy. Without books and movies and music, we would all be stumbling around like Ron, completely ignorant of every other culture, every social, political, or historical experience except our own. Since we have such faith in science: science has proved that art makes us better people. Science has proved that people who read fiction not only improve their own mental health but become proportionally more empathetic. (Really. I wrote an article about this when I was working for a health and wellness magazine in 2012.) If you want a more specific example: science has proved that kids who read Harry Potter growing up are less bigoted. (Here’s an article from Scientific American, so you don’t have to take my word for it.) That is a big fucking deal. Increased empathy can make a life-or-death difference for marginalized people.

But the Defense of Arts and Humanities is about more than empirical data, precisely because you can’t quantify it, unlike a scientific experiment. Art is–in my opinion–literally what makes life worth living. What the fuck is the point of being healthier and living longer and doing all those wonderful things science enables us to do if we don’t have Michelangelo’s David or Rimbaud’s poetry or the Taj Mahal or Cirque de Soleil or fucking Jimi Hendrix playing “All Along the Watchtower” to remind us how fucking amazing it is to be alive and to be human despite all the terrible shit in this world? Art doesn’t just “improve human lives.” Art makes human life bearable.

I hope this answers your question.

To it I would like to add: Please remember that just because you don’t see the value in something doesn’t mean it is not valuable. Please remember that the importance of science does not negate or diminish the importance of the arts, despite what every Republican politician would like you to believe. And above all, please remember that artists are every bit as serious about what they do as astronomers and mathematicians and doctors, and what they do is every bit as vital to humanity, if in a different way. Belittling their work by questioning its importance, or relegating it to a category of lesser endeavors because it isn’t going to cure a disease, or even just making jokes about how poor they’re going to be when they graduate is insensitive, ignorant, humiliating, and, yes, offensive. And believe me: they’ve heard it before. They don’t need to hear it again. We know exactly how frivolous and childish and idealistic and unimportant everyone thinks we are. Working in the arts is a constant battle against the prevailing idea that what you do is useless. But it’s bad enough that the government is doing its best to sacrifice all arts and humanities on the altar of STEM–we don’t need to be reminded on a regular basis that ordinary people think our work is a waste of time and money, too.

Artists are exhausted. They’re sick and tired of being made to justify their work and prove the validity of what they do. Nobody else in the world is made to do that the way artists are. That’s why these questions upset them. That’s why it exasperates me. I have to answer some version of this question every goddamn day, and I am so, so tired. But I’ve taken the effort to answer it here, again, in the hopes that maybe a couple fewer people will ask it in the future. But even if you’re not convinced by everything I’ve just said, please try to find some of that empathy, and just keep it to yourself.

This will explain some of Indian dance methodology.

I sort of suspect this might still play into it - I always remember thinking that shot was weird. Remember the Mistress talking in one of the earlier episodes about how happy she was that she "chose" Clara. It wouldn't surprise me if this came back up as somehow the answer. Not sure how the ring fits in, but it's not like Stephen Moffat has never come up with clever explanations for tiny details before.

Although it might just be a bizarre artifact from using a long lens (or fully zoomed-in zoom lens) with a shallow focus in a fast shot with lots of movement. Nick Hurran's wild, unhinged use of the camera results in a number of bizarre moments, which are usually just kind of charming quirks as a side-effect of his visual flourishes.

When they get out of the painting. -unnoun

The hand is clearly Clara’s - the rings match. (Look a minute or two later, when she’s observing the board.) Whatever’s going on with the camera angle, it’s still clearly Clara.

Oscar Nomination Predictions

Once I get around to finishing up a few of the high-praised films I haven't gotten to (Selma, American Sniper, Mr. Turner, a few others), I'll do a best films list, but I don't think viewing those will change my predictions here too much.

On the other hand, finally seeing Whiplash (which is amazing) convinced me that it has a better chance than I thought, so who knows?

Best Picture The last three years have had nine nominees, so I'll put that many, more or less in order of likelihood. I'll be genuinely shocked if one of the top four doesn't show up. Boyhood Birdman The Imitation Game Selma The Grand Budapest Hotel Theory of Everything Whiplash Gone Girl American Sniper And if there's a tenth nominee, I think it'll be one of these, in this order of likelihood: Foxcatcher - [The enthusiasm for this one seems very limited, but then again, Miller's other two movies (Capote & Moneyball) were more of the "respect" than "love" kinda movies, and they got nominated anyway. He definitely has his fans in the academy. Nightcrawler -A solid Dark Horse here. Unbroken - Opinions are very mixed, and even the positive reactions seem to be in the "good, not great" category. It might get in on sheer "heroic WWII flick" factor, though. Mr. Turner - Unknown enough that it might get lost in the mix, but it's certainly universally praised. Interstellar - Probably wishful thinking to even put it as the "least likely nominee", but I imagine it'll get enough support to have a very, very distant chance. After all, it's been hanging on in the lower parts of the charts to make a good $25 million more than expected. Also, I'd love to see this get an Oscar bump at the box office, which should be enough to get it over $200 million and maybe even in the top 10 of the year. Not that box office or awards matter that much at the end of the day, but it would make this kind of crazy ambitious sci-fi - and original films in general - easier to get through the system. Also, it was awesome. Director

These three seem pretty well locked: Richard Linklater (Boyhood) Alejandro González Iñárritu (Birdman) Ava DuVernay, (Selma) But the last two I'm not sure about at all. I guess this is the order of likelihood to my mind: Wes Anderson - Grand Budapest was fantastic, and dazzlingly made. I imagine Anderson will finally get a directing nod on the "It's his time" vote, but it still might be too quirky to get broad support. Morten Tyldum - The Imitation Game is certainly an excellent film and is going to get a lot of nominations, but the directing seems fairly straightforward. Or maybe it's just a shock that something that middle-of-the-road feeling came from the guy who did [i]Headhunters[/i]. Anyway, it wouldn't surprise me if something flashier got in instead. Clint Eastwood - apparently American Sniper is the usual "rough around the edges but highly effective" thing late-period Eastwood does, which has a way of splitting opinions. Plus, he already has two directing Oscars, so there's not exactly an overwhelming sense of him being under appreciated. Still, he'll probably get a number of votes from older members.

Damien Chazelle - Whiplash is absolutely incredible, and it might pull off the final slot on sheer quality.

David Fincher - This probably depends on how much the Academy actually liked Gone Girl. I have a feeling it's just lowbrow enough that Fincher will miss the shortlist.

Actor Michael Keaton (Birdman) Eddie Redmayne (Theory of Everything) David Oyelowo (Selma) Benedict Cumberbatch (Imitation Game) The top four there are probably locks; certain the top two are. The last slot seems like a battle between Steve Carell (Foxcatcher), Jake Gyllanhaal (Nightcrawler), Ralph Fiennes (Grand Budapest), Bradley Cooper (American Sniper), and Timothy Spall (Mr. Turner). I guess I'll bet on Fiennes, but none of the others would surprise me. I'd really love to see Miles Teller get it for Whiplash, unlikely as that may be.

Actress

Since Hollywood doesn't give enough great leading parts to women, this category is a lot more likely to go to more obscure performances. Julianne Moore (Still Alice) Reese Witherspoon (Wild) Rosamund Pike (Gone Girl) Jennifer Aniston (Cake) Felicity Jones (Theory of Everything) Longshots: Marion Cotillard (Two Days, One Night), Gugu Mbatha-Raw (Beyond The Lights), Shailene Woodley (The Fault In Our Stars), Jenny Slate (Obvious Child)

Supporting Actor JK Simmons (Whiplash) Edward Norton (Birdman) Ethan Hawke (Boyhood) Robert Duvall (The Judge) Chris Pine (Into the Woods) Pine is probably a risky prediction; Mark Ruffalo in Foxcatcher might be a safer bet. I would love Tyler Perry to pull a surprise nomination for Gone Girl, and that's not entirely out of the question.

Supporting Actress

Patricia Arquette (Boyhood) Emma Stone (Birdman) Jessica Chastain (A Most Violent Year) Tilda Swinton (Snowpiercer) Rene Russo (Nightcrawler) Meryl Streep is probably a wiser bet, but I think that would be 100% an "It's Meryl Streep" vote. Then again, she got nominated last year for exactly that. Keira Knightley might get swept in if The Imitation Game has any coattails. (she's very good, but not in a particularly flashy way) Carmen Ejogo (Selma) and Carrie Coon (Gone Girl) are longshots. I've also heard Kristen Stewart is outstanding in Still Alice, and I would love for her to get nominated the same way I want to see Tyler Perry get one.

Original Screenplay

Birdman - Alejandro González Iñárritu, Nicolás Giacobone, Alexander Dinelaris, Armando Bo Boyhood - Richard Linklater The Grand Budapest Hotel - Wes Anderson & Hugo Guinness Dan Gilroy - Nightcrawler Paul Webb - Selma

Mike Leigh might take Nightcrawler's spot for Mr. Turner. The LEGO Movie (Phil Lord & Christopher Miller) and Top Five (Chris Rock) wouldn't shock me. Justin Simien (Dear White People) would be a surprise.

Adapted Screenplay

Gone Girl - Gillian Flynn The Imitation Game - Graham Moore The Theory of Everything - Anthony McCarten Whiplash - Damien Chazelle Snowpiercer - Joon-ho Bong, Kelly Masterson

I doubt Guardians of the Galaxy will get in (if The Dark Knight couldn't nominated), but it'd be a gas if it did.

Communist anon here - Yes to all of them?

@eyeofnewtblog said: I personally would be very interested in hearing an educated opinion on theories and practice

This is going to be a long answer so under a cut it goes. The short answer is no, I do not like either Marxism or communism, to the point where I consider myself anti-communist. The long answer goes under the cut.

First, it’s important to remember where I am coming from, what I am, and what I am not. I’m neither educated in philosophy nor history. I study both, and I have had classes in both, but that doesn’t mean that I’m an expert in either, and my experiences with Marxism have largely been academic, instructors attempting to tell me what Marxism is (fun fact: I once made a lot of these theoretical arguments to a Marxist professor on an exam - I was given an F). So if you’re looking for an educated opinion, depending on what that means, I don’t have one, after all, I got an F on it. Similarly, while I do study some philosophy, it is by no means something I’ve been trained it or seriously articulated; my observations primarily come from observing human nature and studying history and political movements. In that sense, I’m far closer to Eric Hoffer than I am to Hannah Arendt (though both as philosophical scholars far exceed me in every sense that to be compared to them would not be an honor to me but an insult to them). I’m a believer in liberalism and democracy, and a radical individualist, which to me means that people have an inherent dignity, and should be free to determine who they are, what they want to do, and what they value. It’s not a fully-fleshed out philosophy with rules, I’ve already said I’m no philosopher. I just do the best I can and handle situations as they come up.

Those values put me at odds with Marxism from the get-go. Marxism articulates the necessity of a dictatorship, the “dictatorship of the proletariat,” where the government following the revolution seizes the means of production, nationalizing all industries and property, and transition to a communist society, preserving the power of the state to suppress any reactionary or counter-revolutionary activity. I’ve heard this line before; this sounds remarkably similar to authoritarian measures enacted in tinpot dictatorial states meant to preserve order and enforce the power of the government to suppress dissent. The “transitional state” sounds a lot like perpetual “state of emergency” laws enacted to keep the populations in line, a theoretical end-state where such measures are no longer necessary is always on the horizon, but just like the horizon, is never reachable. Call me crazy, but I don’t see how putting people under control of a dictatorship with such unlimited powers is liberating them, save in a metaphorical, dogmatic sense that rationalizes their subjugation as necessary. There’s a broad appeal there, violent mass movements definitely find a lot of support from individuals who see it as a means to finally lord power over those they hate; individuals who want those they despise cowering before them, begging them not to bring the axe down. Such motivations have been an incentive for aspiring foot soldiers to put on their jackboots, so that they eagerly stomp the faces in of the people they despise, and to rationalize it away.

Marxism depends on a lot of things that are untrue, like his assertion that the rate of profit tending to fall, or the labor theory of value which has few serious practitioners and has been widely debunked to the point where Shimshon Bichler was able to criticize the lack of statistical correlation and the degree by which abstract labor must be assumed to see the labor theory of value as purely circular reasoning, hardly compelling for a central tenet of the philosophy to depend on a set of assumptions that rely on others being produced. While I’m no philosopher and reality is impossible to condense into any one singular lens, the degree by which Marxism is riddled with intellectual and logical inconsistencies make it difficult for me as a thinker to take it as seriously as others do. Other matters, while not necessarily untrue, become difficult to function when brought from theory to reality. Take the standard line: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” How are ability and need for each person assessed? What happens if someone is incapable of producing something to the level of ability that is assessed? What happens if someone needs more than is assessed? What happens if need outpaces supply? What happens if ability cannot meet need? What happens if there’s a disaster and there is a temporary shortage? These extend outwards to questions of land use, industrial capacity, training, etc., these centralized economically planned models failed in the 20th century, and again, this turns me off to the model. This is not simply a matter of corrupt Communist Party officials degrading the functioning of the government for personal enrichment, this is a serious information problem that even the most powerful computers of today cannot model and manage, and the idea of a communist state becomes much diminished in appeal to me.

Other stuff in Marxism goes further into what I consider downright repugnant. The idea of “false consciousness” is particularly disgusting to me, where if someone is not motivated by that which the Marxist believes that they should be motivated, these conceptions are deluded and must be corrected. That is such a statement of such monumental arrogance I’m surprised it doesn’t have its own gravity well. It is to say to one person that whatever meaning they have discovered through their own experiences is less valid; it is to say that the Marxist may state that whatever said person values is not in their own benefit. The logical conclusion from this is that non-Marxists cannot be allowed their own judgment, that they must be shaped until they embody the Marxist conception of reality and only then are they truly full people, capable of making judgments of this fashion and assessing what is to their benefit and what is not. For a movement that espouses equality and liberation, sure as hell doesn’t seem very equal to me; only our practitioners are capable, rational beings? No.

Now, most Marxists I know don’t really believe this, but I think this is more of their own conception. Like most practitioners of religions or other philosophies, they pick and choose what tenets to follow.

Communism is practice has been a disaster. Lenin really ran with the idea of the dictatorship of the proletariat with his vanguard model, making the centralizing dictatorship a core part of his leadership and in charge of everything, to the point where failure to provide the dictatorship with what they demanded was considered treason and grounds for termination, and later communist regimes really ran with this idea, as I’ve mentioned before, Marxism appeals to revolutionary dictatorships because it justifies the dictatorship beyond a naked power grab to better secure it. Similarly, Lenin rationalized ignoring his citizens by simply ignoring elections when he lost; the Leninist model was openly a sham democracy. In the Soviet Union, even Khrushchev, who gave the Secret Speech denouncing Stalin, still sent the tanks into Hungary and forcibly medicated any who disagreed with the principles of communism as mentally ill (my previous paragraph is not jumping to conclusions, this was a documented fact). Mao created the “mass line,” a means to consult the population while mandating interpreting their wishes through the ideology, thus dismissing anything that the dictator doesn’t want, a clever fig leaf. Of course, Mao’s already deeply unworthy with its massive loss of life - the Great Chinese Famine was the largest famine in history and enacted by the ideological dogmas of the Great Leap Forward and Mao’s Cultural Revolution was doubling down on his mistakes, murdering those who opposed him. The brutality though, has been the biggest failure; there’s a reason the European left jumped to the social democrat model with the rise of Keynesian economics in the aftermath of World War II, they felt it was a way to achieve their objectives without the brutality of the Soviet model. The totalitarian conception of power and identity left its mark on the movement, but I don’t see them as inventions by power-mad dictators, they were extensions of the philosophy that saw only its practitioners as fully human.

Even discounting the brutality, the standard of living and industrial capacity of communist countries has been low comparatively. In 1927, the Soviet Union produced a scant 3 million tons of steel despite massive advantages in natural resources and manpower, compared to Germany’s 16 million tons, Britain’s 9 million, and France’s 8 million. Relatively speaking, more resources were wasted in steel production in the USSR, and this was similar across the board in communist countries. Communism lambasted capitalism for its wastefulness, but the numbers show that communism was the far more wasteful, inefficient method of economic organization. Some defenders of the Soviet Union point to the growth under leaders like Khrushchev, but I counter that the exceptional rate of growth was both temporary and comparatively small compared to non-communist states. Francis Spufford may have tried to sell it with the idea of Red Plenty as a fusion of history and fiction, but history has borne out that it was entirely fiction.

The more anarchist sects of the movement, the ones who reject the transitional state, similarly were failures in practice. In Spain, those who did not wish to join were often brutalized, which seems to me to be violating the principal of anarchism in that forced compliance in an anarchist society is an extension and use of state power. This is relatively common throughout history though, particularly when it comes to ideology. The Soviet Union decried “imperialism” but was incredibly imperialist, just as the United States decried the security state apparatus of the Soviet Union as violating the rights of their own citizens while pursuing COINTELPRO when it came to folks like Fred Hampton. In a more practical sense, the anarchists poor training and suboptimal deployment were unable to stop Franco despite having plenty of clear advantages in the Spanish Civil War. While they are by no means the only reason for the Republican failure, the inability for the anarchist faction to defend their people is a failure of their system of government. A lot of anarchist models run into this problem, it should not be thought of as a failure reserved solely for the anarcho-communist model, and anyone who says it doesn’t is ignoring history.

So to sum up, I consider Marxism to be a philosophy which espouses tenets that I find disgusting, and it’s articulation of government to be illiberal, anti-democratic, and founded on the violation of human rights and dignity.

Thanks for the question, Anons who were waiting.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

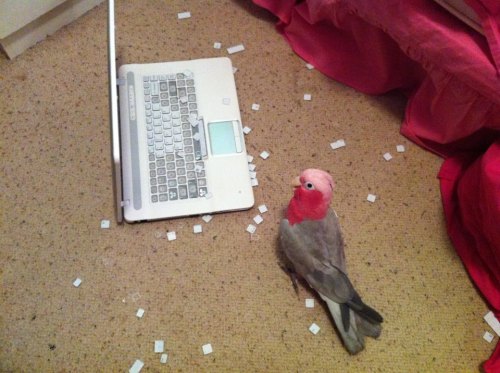

my friend left her window open in her bedroom and came back to find this

look at his self-satisfied little face, the cheeky shit

motherfucking australia

rb to relieve the back pain of the person u reblogged this from

as a member of the lgbt community, it really hurts to hear people say that my "lifestyle" isn't "family friendly". i care a lot about being family friendly. it's very important to me. that's why this month i'm partnering with your mom -

On the other hand, Hayles' script for The Celestial Toymaker was completely rewritten by Donald Tosh (including using the Mandarin second meaning of the title), to the point where Hayles was supposed to just be credited for the idea. Which was then again completely rewritten by Gerry Davis to the point where Tosh refused to take credit, and Hayles was ultimately credited on a technicality.

Similarly, Letts and Dicks had Hayles completely revamp his Monster of Peladon script once, and then Dicks did was was apparently a pretty major rewrite of his own.

Which is to say, doesn't it almost seem like cheating to choose a guy whose bad scripts were basically written by other people?

On the other hand (or back on the original hand?), that's a lovely essay.

Which writers have written the Doctor Who episodes most varied in quality? Gaiman? Aaronovitch?

This is framed interestingly, and I like it.

The two proposed are, of course, writers of two episodes of decidedly different receptions. But both have an all-time classic and a lesser work. Neither Nightmare in Silver nor Battlefield are unwatchable lows of the series that curl your toes and make you wish you had never taken that DVD off the shelf, and Doctor Who has those.

But by picking writers who have done more than two stories, you can get ones who have written things that are the equal of The Doctor’s Wife and Remembrance of the Daleks and who have also written ungodly horrors. There is a perspective in which it is hilarious that the writer of Listen also wrote The Doctor, The Widow, and the Wardrobe. Robert Holmes presents himself as another good target here. The mighty writer of The Ark in Space and Carnival of Monsters, the genius behind The Ribos Operation and The Deadly Assassin, who also gave us The Krotons. Though I actually like that one, so let’s do The Mysterious Planet. Or The Power of Kroll. Ouch. I mean, have you sat down and watched The Power of Kroll lately, because I fucking won’t. I will not sit down with that voluntarily. There’s no reason to do that to a man more than once.

Of course, in that regard, the really tempting answer is Robert Holmes for The Talons of Weng-Chiang and The Talons of Weng-Chiang, that being the single most pathological object in the history of Doctor Who. I mean, don’t get near a discussion of something so complex as rape culture with someone who doesn’t get that this is something you should be embarrassed to have on your DVD shelf because it is fucking called The Talons of Weng-Chiang. And yet, of course, it is full of witty dialogue and charming atmosphere, and is brilliant and beautiful and feels exactly like 1970s Doctor Who costume drama should feel, and on top of that it has that gorgeous giant rat, which you look at and your heart breaks and you just think, “oh, bless you for even trying, Philip Hinchcliffe, bless you for even trying.”

But that is, perhaps, too esoteric a point. It is a clever answer, and would satisfy the question, but one suspects that The Power of Kroll was the more revealing option.

In other words, I think you get the really interesting results when you look at stories that are among the absolute worst ever. Sure, some of them are by one-flop-wonders like Anthony “exploding typewriter” Steven, but others are things like The Dominators, written by the same people who brought us The Web of Fear. And while The Web of Fear is not the outstanding miracle that people think it is, and is self-evidently inferior to the story before it, it is a fuck of a lot better than the sodding Dominators. In this regard it is also tempting to say something like Planet of the Dead and Army of Ghosts/Doomsday, if only to make a point about rewrites.

Similarly, a really strong case can be made for Terry Nation, who really does swing into the extremes. I mean, there’s no excuse for some of Nation’s not-in-any-meaningful-sense-scripts… but Genesis of the Daleks really is good. So are the first two, even if there’s no real reason to have tried the tentacle monsters in the first place. He embodies the ridiculous and the sublime of Doctor Who in the same way that The Talons of Weng-Chiang does, but he does it with astonishing gulfs in basic visual literacy.

But another name jumps out, and I think it is particularly worthwhile. Brian Hayles, who is credited with both The Celestial Toymaker and The Monster of Peladon, is the rare writer to land two stories on the all-time worst list, and I’m willing to say that even if we apply the Talons of Weng-Chiang principle. To either of them. And yet between them he has The Ice Warriors, The Seeds of Death, and The Curse of Peladon, two of which are absolutely fantastic things that just thinking about makes me want to watch again, and the third of which I’ll admit is worth a revisit once every couple of years.

Because, I mean, they weren’t stories I ranted and raved about like I did in my “holy shit how is this not one of the all-time classics of the Patrick Troughton era” of Enemy of the World, but that’s still just caught up in the gulf between people who think the point of the Troughton era was the monsters and the people who think the point of it was that it started with Power of the Daleks. But The Ice Warriors is the sort of thing that proves that the base under siege could work. You can do gripping tension with relative cheapness. The Ice Warriors is an incredibly smooth viewing experience, and was even before the animation. And The Curse of Peladon, man, that’s just a beautiful, mad thing that only Doctor Who would ever do. There’s a Doctor Who tradition that consists of that, The Ribos Operation, and Warrior’s Gate that you just constantly hope they’ll try again. (Period alien planets. Work every time. Well. Every time that it isn’t The Monster of Peladon.)

That’s a very, very strange gulf in quality there, purely because of the widely varied circumstances of all of them. And I really do think it’s the widest, simply because of how passionately I am personally led to love and hate the particular extremes. And the weirdness that there’s a Peladon story at each end too.

Yeah. Brian Hayles.

-

gotong-royong reblogged this · 1 week ago

gotong-royong reblogged this · 1 week ago -

abraxax-heart reblogged this · 1 week ago

abraxax-heart reblogged this · 1 week ago -

byesad liked this · 1 week ago

byesad liked this · 1 week ago -

scientificapricot liked this · 1 week ago

scientificapricot liked this · 1 week ago -

midnightsunrise13 liked this · 1 week ago

midnightsunrise13 liked this · 1 week ago -

timekiller024 reblogged this · 1 week ago

timekiller024 reblogged this · 1 week ago -

timekiller024 liked this · 1 week ago

timekiller024 liked this · 1 week ago -

ame-exe reblogged this · 1 week ago

ame-exe reblogged this · 1 week ago -

ame-exe liked this · 1 week ago

ame-exe liked this · 1 week ago -

zeloinator liked this · 1 week ago

zeloinator liked this · 1 week ago -

theviolinonfire reblogged this · 1 week ago

theviolinonfire reblogged this · 1 week ago -

theviolinonfire liked this · 1 week ago

theviolinonfire liked this · 1 week ago -

standardhdmicable reblogged this · 1 week ago

standardhdmicable reblogged this · 1 week ago -

ronjaendf liked this · 1 week ago

ronjaendf liked this · 1 week ago -

rhyme-draws-stuff liked this · 1 week ago

rhyme-draws-stuff liked this · 1 week ago -

lovely-malice liked this · 1 week ago

lovely-malice liked this · 1 week ago -

arkagrzewczawpz liked this · 1 week ago

arkagrzewczawpz liked this · 1 week ago -

prettypinklilies reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

prettypinklilies reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

prettypinklilies liked this · 2 weeks ago

prettypinklilies liked this · 2 weeks ago -

strngedve liked this · 2 weeks ago

strngedve liked this · 2 weeks ago -

mannleemann reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

mannleemann reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

silverthief22 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

silverthief22 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

silverthief22 liked this · 2 weeks ago

silverthief22 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

severalmoremutants liked this · 2 weeks ago

severalmoremutants liked this · 2 weeks ago -

ct4051 liked this · 2 weeks ago

ct4051 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

dreaming-notsleeping reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

dreaming-notsleeping reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

rainstorms-by-june liked this · 2 weeks ago

rainstorms-by-june liked this · 2 weeks ago -

firlen liked this · 2 weeks ago

firlen liked this · 2 weeks ago -

mickiperspicacious liked this · 2 weeks ago

mickiperspicacious liked this · 2 weeks ago -

thestarschasethesun reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

thestarschasethesun reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

unopioniatedcarnivalgoldfish liked this · 2 weeks ago

unopioniatedcarnivalgoldfish liked this · 2 weeks ago -

eulaliafluffboll reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

eulaliafluffboll reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

cuttlefishjoe reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

cuttlefishjoe reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

idafloreak liked this · 2 weeks ago

idafloreak liked this · 2 weeks ago -

animefreak44 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

animefreak44 reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

animefreak44 liked this · 2 weeks ago

animefreak44 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

flitterflappers reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

flitterflappers reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

stubbornheartache liked this · 2 weeks ago

stubbornheartache liked this · 2 weeks ago -

fyuschia liked this · 2 weeks ago

fyuschia liked this · 2 weeks ago -

snowbelle liked this · 2 weeks ago

snowbelle liked this · 2 weeks ago -

saturnisfilledwithbees reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

saturnisfilledwithbees reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

saturnisfilledwithbees liked this · 2 weeks ago

saturnisfilledwithbees liked this · 2 weeks ago -

himynameisstonedwhatsyours reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

himynameisstonedwhatsyours reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

nerdvanauniverse reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

nerdvanauniverse reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

thesebattlescarsarebeautiful liked this · 2 weeks ago

thesebattlescarsarebeautiful liked this · 2 weeks ago -

auxphonographic-dysphonia liked this · 2 weeks ago

auxphonographic-dysphonia liked this · 2 weeks ago -

auxphonographic-dysphonia reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

auxphonographic-dysphonia reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

sinnamonbunnies reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

sinnamonbunnies reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

sinnamonbunnies liked this · 2 weeks ago

sinnamonbunnies liked this · 2 weeks ago -

a-king-named-lear reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

a-king-named-lear reblogged this · 2 weeks ago