Gillian Anderson As Morticia Addams, Photographed By Mark Seliger In 1997.

Gillian Anderson as Morticia Addams, photographed by Mark Seliger in 1997.

More Posts from Otherworlding and Others

Concept paintings for 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (1968).

The interesting world of medieval manuscripts. I’ve always wondered what a medieval Yoda would look like...

Bart Nixon, designer of Pennywise the Dancing Clown from Stephen King’s IT (1990).

The art of outer space: nebulae photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope. It sure is brimming with activity up there.

Illustrations by Russian artist, Gennady Kalinovsky for a 1974 edition of ALICE IN WONDERLAND.

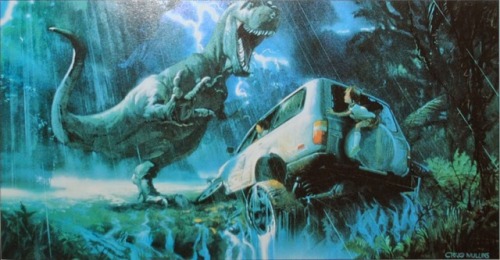

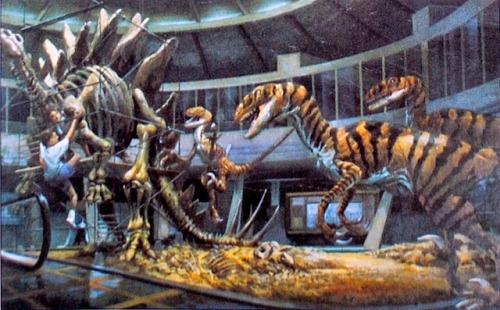

Concept art for Jurassic Park (1993) by Craig Mullins (images 1 and 3), and David J Negron (2 and 4).

Everybody was talking about Jurassic Park at the time. It was that kind of film (everything is much more fragmented these days). The T-Rex was like the T-1000, an obvious breakthrough, a new Eighth Wonder. Audiences hadn’t seen that before: a walking, breathing dinosaur. It was as if dinosaurs roamed the Earth again.

A Marilyn Monroe robot, by Japanese inventor, Shunichi Mizuno. 1982.

No thank you.

(Images from the great site, Cybernetic Zoo.)

Ian Miller cover art for THE HAUNTER OF THE DARK AND OTHER STORIES (1974).

Mall interiors from the 1970s/1980s.

My mother hated them, but to me, a kid, malls were exciting. They looked like small sci-fi colonies mixed with ocean liners, with their blood-red carpets, gilded railings, jungle plants, and crooked floor patterns. The mall, that’s where you found your precious toys. It’s where humans lived, and promises were fulfilled. Take an 1980s teen flick, and there’s a scene in a mall.

George A. Romero’s DAWN OF THE DEAD shows one in all its kitschy glory.

I was about 12, when I saw her again: she was hanging out with her friends near the fountain. A blonde elf-like girl, the sun around which the other kids orbited, she laughed a lot. Whenever her friends laughed though, she seemed quiet, troubled even, biting her thumb; that’s when her eyes caught me. In a dark corner, two 16-year-olds, who seemed like real adults to me, were playing an arcade game and eating french fries; I wondered how they could play with greasy fingers. One burped loudly, but they didn’t laugh. Eyes on the game.

Suddenly these two kids rush past you on their bikes. You know one of them, he is an enemy. He gave you the finger once, the first time you saw anyone making that gesture. “Asshole,” he says. Someone tells them they can’t ride their bikes here, they shout something back.

Gino is this thin, moustached hothead with tight stonewash jeans and big white sneakers, and a permed mullet. He doesn’t walk, he bounces, like a Muppet; he moves fast, like someone who’s on his way to punch someone. He smokes and has a gold-colored necklace with his name, but better not joke about it, because Gino is the kind of guy who doesn’t get jokes. Your brother referred to him once as “Evil Freddie Mercury”. He always seems to be everywhere: when you go ice skating, you run into him there; when you go swimming, he’s at the pool; when you’re playing football in the field behind your school you know he’s going to show up. He looks at you—whenever you look at him, his eyes always immediately shoot back—but he leaves you alone and trots out of sight. You’re vaguely relieved to see him go.

The wall with flickering TVs plays an MTV video, you kind of watch as you wait for your mother to return, but not really. The two 16-year-olds have finished their game, they mumble some curses, one smacks the arcade machine, and they leave. You see Sebastian’s mother—Sebastian, the kid who stole money once. She passes you and you feel her eyes, but you pretend not to see her.

The lady in her mobility scooter, her bags of groceries tied to the handlebars. She is rotund and can hardly walk, and always takes the elevator. Sometimes people help her get in, more often they don’t. You cracked cruel jokes about her once when you were here with your brother, but really you just felt sadness.

You realize every kid is there with friends except you, and just when you’re about to discover some great truth about yourself and the world around you, your mother returns and you go home, your toys in the plastic toy store bag that you tried to hide from the blue eyes of the elegant blonde elf, who’s still laughing with her friends, and who, though nobody would have guessed it, would go on to play such a major part in your life years later.

These are just some memories I have of the mall. Stories of my childhood unfolded there, and I remember everything.

ALICE IN WONDERLAND by sci-fi and fantasy illustrator, Rodney Matthews.

-

againstadarkbackground liked this · 2 months ago

againstadarkbackground liked this · 2 months ago -

againstadarkbackground reblogged this · 2 months ago

againstadarkbackground reblogged this · 2 months ago -

mtthwclmnt liked this · 2 months ago

mtthwclmnt liked this · 2 months ago -

bonelady liked this · 2 months ago

bonelady liked this · 2 months ago -

travestipunk liked this · 2 months ago

travestipunk liked this · 2 months ago -

alliswyattonthewesternfront reblogged this · 2 months ago

alliswyattonthewesternfront reblogged this · 2 months ago -

lovekviryou liked this · 3 months ago

lovekviryou liked this · 3 months ago -

lovekviryou reblogged this · 3 months ago

lovekviryou reblogged this · 3 months ago -

aracnes reblogged this · 4 months ago

aracnes reblogged this · 4 months ago -

whispersinthecosmos reblogged this · 4 months ago

whispersinthecosmos reblogged this · 4 months ago -

whispersinthecosmos liked this · 4 months ago

whispersinthecosmos liked this · 4 months ago -

otherworlding reblogged this · 4 months ago

otherworlding reblogged this · 4 months ago -

bacour liked this · 5 months ago

bacour liked this · 5 months ago -

facebookselfies liked this · 5 months ago

facebookselfies liked this · 5 months ago -

eskvarr reblogged this · 7 months ago

eskvarr reblogged this · 7 months ago -

cutebronto reblogged this · 7 months ago

cutebronto reblogged this · 7 months ago -

risingphoenix761 reblogged this · 7 months ago

risingphoenix761 reblogged this · 7 months ago -

cheapsweets liked this · 7 months ago

cheapsweets liked this · 7 months ago -

thealmanachofreblogs reblogged this · 7 months ago

thealmanachofreblogs reblogged this · 7 months ago -

spidermonkey40s reblogged this · 8 months ago

spidermonkey40s reblogged this · 8 months ago -

spidermonkey40s liked this · 8 months ago

spidermonkey40s liked this · 8 months ago -

lisakitto reblogged this · 8 months ago

lisakitto reblogged this · 8 months ago -

sumtingfersher liked this · 8 months ago

sumtingfersher liked this · 8 months ago -

zackdexter123123 liked this · 8 months ago

zackdexter123123 liked this · 8 months ago -

nimeve liked this · 8 months ago

nimeve liked this · 8 months ago -

nimeve reblogged this · 8 months ago

nimeve reblogged this · 8 months ago -

its-sorcery reblogged this · 8 months ago

its-sorcery reblogged this · 8 months ago -

its-sorcery liked this · 8 months ago

its-sorcery liked this · 8 months ago -

springiwithkampfstiefels reblogged this · 8 months ago

springiwithkampfstiefels reblogged this · 8 months ago -

oshacompliantmagicalgirl reblogged this · 8 months ago

oshacompliantmagicalgirl reblogged this · 8 months ago -

ayanato-vampi reblogged this · 8 months ago

ayanato-vampi reblogged this · 8 months ago -

politoke reblogged this · 8 months ago

politoke reblogged this · 8 months ago -

femmeabyss reblogged this · 8 months ago

femmeabyss reblogged this · 8 months ago -

femmeabyss liked this · 8 months ago

femmeabyss liked this · 8 months ago -

nicerumors liked this · 8 months ago

nicerumors liked this · 8 months ago -

maiholic reblogged this · 8 months ago

maiholic reblogged this · 8 months ago -

gothfrog-44 reblogged this · 8 months ago

gothfrog-44 reblogged this · 8 months ago -

gothfrog-44 liked this · 8 months ago

gothfrog-44 liked this · 8 months ago -

shadow-banned-the-hedgehog reblogged this · 8 months ago

shadow-banned-the-hedgehog reblogged this · 8 months ago -

sirquacklesdefoof liked this · 8 months ago

sirquacklesdefoof liked this · 8 months ago -

peggycarterisbetterthanme reblogged this · 8 months ago

peggycarterisbetterthanme reblogged this · 8 months ago -

mica5fowl reblogged this · 8 months ago

mica5fowl reblogged this · 8 months ago -

shubaka reblogged this · 8 months ago

shubaka reblogged this · 8 months ago -

brokenxmachine liked this · 8 months ago

brokenxmachine liked this · 8 months ago -

maeglinthebold reblogged this · 8 months ago

maeglinthebold reblogged this · 8 months ago -

howling-at-night reblogged this · 8 months ago

howling-at-night reblogged this · 8 months ago -

mildmoderngirl liked this · 8 months ago

mildmoderngirl liked this · 8 months ago -

ryanseanw reblogged this · 8 months ago

ryanseanw reblogged this · 8 months ago